Scientific and legal elements :

Organ transplant practices have developed considerably since the 1950s, thanks to discoveries made it possible to remedy the phenomenon of transplant rejection. According to the Biomedicine Agency, 5891 organ transplants were performed in 2016, of which 4937 are kidney or liver transplants. From 2012 to 2016, the number of transplants increased by 17%. The vast majority of transplants are performed postmortem[1].

The law regulates the practice of organ removal. On the transplant recipient’s side, the operation must have a serious chance of success, not involve disproportionate risks and represent a real prolongation of life for the recipient[2]. On the donor’s side, the donor may be alive or deceased.

As regards organ donation between living persons, bioethics laws have constantly extended the circle of potential donors who, in all cases, must have the legal capacity to consent, in particular be of legal age. In 1994, the circle was limited to the nuclear family: parents, children, siblings, possibly spouse. In 2004, cousins and allies joined this circle, as did “any person providing proof of at least two years of living together with the recipient”. The law of 7 July 2011 went even further by including “any person who can prove a close and stable emotional link with the recipient for at least two years”. It also authorized “cross-donation” of organs between two donor/recipient pairs, each meeting the relational conditions of organ donation and transplantation but not compatible.

For sampling from a deceased person, the first requirement is to ensure that the person is dead. The Public Health Code generally requires three checks to establish that a person with “persistent cardiac and respiratory arrest” is dead: total absence of consciousness and spontaneous movement; abolition of all brainstem reflexes; total absence of spontaneous breathing[3]. If the person is on ventilatory support and blood flow continues to a certain degree, further tests are needed to ensure that the entire brain is irreversibly destroyed[4]. However, since a decree of August 2, 2005 (n°2005–949), the removal of a kidney or a liver can be carried out on persons recognized dead simply following “a persistent cardiac and respiratory arrest[5]”. Since 2014, certain hospitals based on the 2005 law have been performing organ removal from a deceased person following a decision to limit or stop treatment.

Since the Health Act of 26 January 2016, it is sufficient that the deceased person has not registered on the National Register of Refusals to indicate his opposition to organ removal, or that he has not explicitly expressed his refusal in another form, for removal to be possible (this is referred to as “deemed consent”). The doctor must simply “inform” the relatives of the nature and purpose of the planned sample.

Despite the increase in transplants, not all requests are met. Hence the question of relaxing the rules regulating the practice of organ harvesting and transplantation, in particular the principles of anonymity, free donation and consent to donation[6].

Anthropological and Ethical Issues

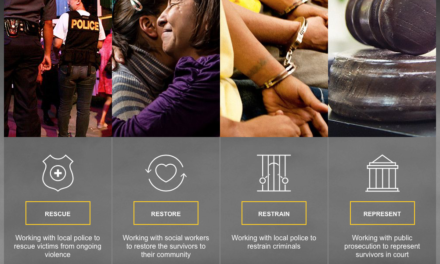

Organ donation always involves painful human situations. Faced with these situations of suffering, we must foster a culture of giving in our society. Adult citizens should also be encouraged to explicitly declare their possible consent to a donation and to prepare their families for it. However, a purely quantitative reasoning on organ needs to justify the extension of transplant possibilities is too narrow in relation to the personal and family issues involved.

The current “deemed consent” regime, which governs organ donation from a deceased person, is atypical in law. It is contrary to the Hospitalized Patient Charter, which, for therapeutic acts, requires a priori “free and informed” consent on the basis of “accessible and fair” information. On 26 June 2014, the European Court of Human Rights ruling “Petrova v. Latvia” stated: “National legislation which by lack of clarity makes it possible to remove an organ from a public hospital without the consent of the family violates Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights on respect for private and family life.

Such an atypical rule requires strengthened safeguards to ensure that consent does not become “imposed” from “presumed”. In this context, the collection of information from families should be a rule, the family unit being the first circle of solidarity. The law giving the right to public medicine to remove organs on the basis of presumed consent only, without consultation with the family, tends to nationalise the body, in flagrant contradiction with the patient’s freedom, and without there being any real expression of solidarity. Rather, a true donation ethic should be encouraged[7].

Furthermore, the removal of organs from a deceased person can be done not only for therapeutic purposes but also for scientific (research) purposes[8]. It is not respectful of the citizen that these distinct and specific purposes are subject to the same procedure. If special solidarity is required from the citizen to help other people, each citizen is free to refuse such or such research (as provided for in the Hospitalized Patient Charter for research on living patients).

Should we then ask ourselves whether we should return to the explicit consent regime? At a minimum, in the “deemed consent” regime, family notification is essential to ensure consent. Although medical teams are still trying to obtain this opinion, it is regrettable that the 2016 law no longer requires them to do so.

Finally, among living donors, the successive enlargement of potential donors could encourage a certain form of organ trafficking. On the one hand, the notion of “close and stable emotional bond” is vague and difficult to arbitrate by the courts, a passage required by law for organ transplant authorization. On the other hand, the possibility of integrating individuals into the “cross-donation” circuit risks encouraging financial motivation[9]. The risk of such a drift would increase if the principle of free donation were called into question.

Is the non-expression of a refusal sufficient to characterize a “gift”? To encourage organ donation, information campaigns should be promoted that promote registration in a register where everyone could clearly express their consent to or opposition to the removal of some of their organs in the event of death, in the spirit of the “advance directives” (see fact sheet on the end of life).

February 1, 2018

[1] https://www.agence-biomedecine.fr/IMG/pdf/cp_activite-greffes-organes-2016_agence-biomedecine.pdf

[2] cf. Code de la Santé Publique (CSP), article L1211‑6.

[3] CSP, article R. 1232–1.

[4] CSP, article R. 1232–2.

[5] Cf. CSP, article R. 1232–4‑1.

[6] Cf. CCNE, Dossier de presse, « Les thèmes des États généraux », fiche n°2, 18 janvier 2018.

[7] Cf. discours de Benoit XVI sur le don d’organes du 7 novembre 2008.

[8] CSP, L1232‑1.

[9] Cf. J.-R. BINET, La réforme de la loi bioéthique. Commentaire et analyse de la loi du 7 juillet 2011, LexisNexis « Actualité », 2012. Voir aussi J.-R. BINET, Droit de la bioéthique, LGDJ, 2017, pp. 212–235.