Les avancées des biotechnologies permettent de réaliser ce qui relevait jusqu’ici du fantasme, débouchant sur de multiples vertiges. Vertige de l’origine: un enfant peut être issu d’un don de sperme, d’un don d’ovule, d’un don d’embryon ou d’une gestation par autrui, créant ainsi de nouvelles filiations. Vertige de la différence: à travers la procréation dans des couples de femmes ou par des femmes seules, dans des couples d’hommes ou par des hommes seuls, ou encore chez les transgenres. Vertige de la prédiction: à travers un lien possible entre procréation et prédiction, qui pourrait occuper de plus en plus de place à l’ère du séquençage du génome.

Ces possibilités technologiques peuvent fasciner autant qu’elles peuvent être source de perplexité, voire d’angoisse. Mais elles peuvent surprendre aussi par les nouvelles origines qu’elles rendent désormais possibles et qu’il s’agit d’ac- compagner en composant avec un monde qui s’invente parfois plus vite que notre capacité à le suivre.

C’est sur ce thème que s’est exprimé à Sion, en Valais, en septembre 2018, François Ansermet, professeur honoraire à l’Université de Genève (UNIGE) et à l’Université de Lausanne (UNIL), après avoir été d’abord professeur ordinaire de pédopsychiatrie, vice-doyen de la Faculté de biologie et médecine à l’UNIL, médecin-chef au Service universitaire de psychiatrie de l’enfant et de l’adolescent au Centre hospitalier universitaire vaudois (CHUV), puis professeur ordinaire de pédopsychiatrie à l’UNIGE et, sur le plan hospitalier, chef du Service de psychiatrie de l’enfant et de l’adolescent aux Hôpitaux universitaires de Genève (HUG), ainsi que directeur du Département universitaire de psychiatrie à la Faculté

de médecine de l’UNIGE. Il faut ajouter à ce palmarès que François Ansermet est membre du Comité consultatif national d’éthique, à Paris, depuis 2013.

Pour François Ansermet les droits de l’en- fant sont aujourd’hui au centre des préoccupations de la psychiatrie de l’enfant et de l’adolescent. L’enfance construit le monde de demain. Mais sera-t-il possible d’être enfant demain dans le monde tel qu’il est en train d’évoluer ? C’est la grande question que pose le professeur. Le mariage pour tous, dans un certain nombre de pays par exemple, a débouché sur la question de la procréation pour tous qui soulève d’importantes résistances, tout comme les problématiques de la génomique et de l’intelligence artificielle.

“L’enfance construit le monde de demain. Mais sera-t-il possible d’être enfant demain dans le monde tel qu’il est en train d’évoluer ?”

Tous ces thèmes, a fait remarquer le professeur Ansermet, font l’objet de prises de position collectives, y compris de la part des milieux religieux. Le curseur du symbolique court plus vite que nous, ce qui pour autant ne doit pas être interprété comme une crise. Les résistances face au nouveau sont compréhensibles et il faut reconnaître que ce nouveau existe et que l’enfance nous regarde.

Les biotechnologies impliquent de nouveaux modes de procréation. Il s’agit de créer de la vie dans un monde qui crée aussi de la mort – par des guerres, des crimes, des racismes. Il ne faut donc pas tomber dans le catastrophisme, a mis en garde le professeur Ansermet qui a rappelé l’importance des mythes et des religions qui de tout temps ont thématisé sur la création de la vie. Bien avant les procréations médicalement assistées il y a eu des procréations divinement assistées, bien au-delà du biologique. Dans « La Légende dorée » de Jacques de Voragine, à l’époque de la Renaissance – un ouvrage qui a porté l’inspiration des peintres du quattrocento – il est dit que Dieu peut créer l’homme de quatre façons: sans l’homme ni la femme, comme il le fit pour Adam; par l’homme sans la femme, comme il le fit pour Ève; par la femme sans l’homme, comme cela s’est produit miraculeusement suite à l’Annonciation à la Vierge Marie, qui est d’abord la fête de l’Incarnation puisque Dieu commence en Marie sa vie humaine qui conduira Jésus jusqu’à la Croix et la Résurrection, jusqu’à la Gloire de Dieu – voir « La Divine comédie » de Dante: « Ô Vierge mère, fille de ton fils ». Avec les biotechnologies, a souligné le professeur Ansermet, nous sommes bien en deçà de ce que l’imagination des humains a pu construire sur le mystère de l’origine, sur le mystère de venir au monde. Enfin, le quatrième mode de création de l’homme évoqué dans « La Légende dorée » est « par l’homme et la femme selon la manière commune ». Au nombre des mythes ayant pour sujet la création de la vie, on peut citer Athéna sor- tant, toute armée, de la tête de Jupiter et Dionysos né deux fois, du ventre de Sémélé et de la cuisse de Jupiter.

Le monde de la procréation change plus vite que notre capacité à le suivre, a fait observer François Ansermet. Que sont donc ces biotechnologies qui bouleversent nos esprits ? Il est vrai que ces biotechnologies et leurs impacts font l’objet, à raison, d’une certaine perplexité de la part du public. Loin de la vision romantique de la science dont les avancées permettent la conception et la mise en œuvre de nouveaux traitements médicaux, il convient de s’interroger aujourd’hui sur ces technologies de la procréation qui opèrent sur le monde sans que nous sachions exactement de quoi il en retourne. Il peut être en effet extrêmement inquiétant de penser qu’on dispose de techniques opérant sur la réalité et dans le même temps ignorer quel produit en sortira. Ces démarches technologiques peuvent conduire à du non-savoir. En résulte un monde fabriqué, inventé, inédit dont ne nous savons pas ce qu’il est. Raison pour laquelle les questions issues des découvertes technologiques actuelles sont de plus en plus traitées au sein de comités d’éthique, véritables observatoires de la perplexité et de l’angoisse contemporaines, soit des observatoires de ce que nous ne pouvons représenter.

Pour François Ansermet, face à l’irreprésentable, face à ce qui laisse perplexe et angoisse, deux types de réaction sont possibles. D’un côté les techno-prophètes annoncent un monde nouveau dans lequel il sera possible de procréer même si l’on est infertile et de sélectionner des enfants qui ne souffriront pas de maladies. Ceux-ci nous promettent un monde meilleur. De l’autre se trouvent les bio-catastrophistes qui font valoir que si l’on touche à la nature, on touche à la loi, avec l’idée d’une superposition de la loi naturelle et de la loi morale. Il y aurait ainsi transgression de la nature au moyen de ces technologies. Pour le clinicien, l’enjeu est bien d’être à la hauteur du temps que nous vivons. Il convient, selon lui, de ne pas se laisser enfermer dans une tentation conservatrice et de ne pas maudire son époque. Il faut délibérément regarder vers l’avenir plutôt que s’accrocher au passé. D’une part ne pas craindre l’incertitude et d’autre part ne pas succomber à la tyrannie du passé. Et arriver à se situer dans ces deux dimensions.

Les nouveaux modes de procréation médicalement assistée du type de la fécondation in vitro, de l’injection intra-cytoplasmique de spermatozoïdes, de la conservation d’ovocytes, du diagnostic pré-implantatoire et pré-conceptionnel, de la procréation posthume et autres sur- prennent, étonnent, dérangent, bousculent et produisent un vertige. Pour François An- sermet, un vertige qui angoisse et attire à la fois, un vertige source de fascination. Les médias ne se privent pas d’ailleurs de nous raconter par le menu des cas de procréation assistée totalement ahurissants. Rien d’étonnant à cela puisqu’ils titillent une corde qui nous est à tous particulièrement sensible, celle de notre origine qui va de pair avec la Sexualité avec un grand S – le grand mot qui émoustille est lâché.

“Et c’est bien la question que posent tous les enfants: pourquoi suis-je moi et pas quelqu’un d’autre ?”

D’où vient ce vertige, ou plutôt ces vertiges ? Car pour François Ansermet, il y en a trois: le vertige de l’origine, le vertige de la différence des sexes dans la procréa- tion et celui de la prédiction. À propos du premier, le vertige de l’origine, le professeur Ansermet tient à rappeler que le monde

de l’origine, symbolique et imaginaire, est différent du monde de la sexualité. Or le problème réside dans le fait que nous vivons dans une ère de paradigmes très biologiques et que nous avons tendance à penser que origine est égal à sexualité, que procréation est égal à gestation, que naissance est égal à filiation alors que tous ces mondes sont disjoints. Le plus irreprésentable de cette série est certainement la procréation. Quand se produit-elle ? Quel est son moment M ? Quand la vie est-elle créée ? Même les biologistes travaillant dans des centres de procréation médicalement assistée sont très hésitants sur la question de l’émergence de la vie, à savoir lorsque des cellules se combinent puis viennent à se multiplier. D’où vient cette étincelle ? Pour François Ansermet, la question fondamentale sur laquelle tout le monde bute, y compris les biologistes et les médecins de la reproduction, est la suivante: d’où viennent les enfants ? Freud jugeait que c’était la question impossible par excellence. Et c’est bien la question que posent tous les enfants: pourquoi suis-je moi et pas quelqu’un d’autre ? Pourquoi ici plutôt qu’ailleurs ? François Ansermet s’est plu à citer l’histoire d’une petite fille de 8 ans dont la mère est enceinte. Au petit-déjeuner la mère fait une tartine au miel pour sa fille. Celle-ci regarde le ventre de sa mère et lui demande qu’est-ce que c’est que « ça ». La mère lui répond qu’elle attend un nouvel enfant. « D’où vient cet enfant ? » demande la petite. La mère tente une explication: le papa et la maman, le baiser, la petite graine. « Quand tu vois ce miel sur cette tartine, pense aux abeilles, aux fleurs, au pollen… » La petite fille coupe alors sa maman: « Arrête avec ces explications complètement nulles. À l’école on a déjà eu des cours d’éducation sexuelle, on sait exactement de quoi il s’agit. Je ne te demande pas quelle position tu as adoptée avec papa pour avoir ce nouvel enfant. »

La mère transpire, les gouttes de sueur tombent sur la tartine de miel. « Qu’est-ce que tu veux savoir finalement », s’énerve

la mère. Et la petite fille de répondre très fermement: « Avant d’être dans ton ventre, où est-ce que j’étais ? » Pour le professeur Ansermet, la beauté de cette question est un émerveillement: « C’est comme pour un mort, on dit que son corps est en terre, son âme est au ciel; les enfants disent: OK. Mais moi quand je serai mort, quand mon corps sera en terre, quand mon âme sera au ciel, moi, où est-ce que je serai ? »

Pour François Ansermet, le problème majeur posé par les technologies de la procréation médicalement assistée est qu’elles sont sources de disjonctions. On sépare la sexualité de la procréation, la procréation de la gestation, la gestation de la naissance — on peut passer par une gestation pour autrui avec une mère porteuse — on sépare enfin l’origine de la filiation — par dons de sperme, d’ovules, d’embryons, des doubles dons et, faut-il encore ajouter, créer une disjonction temporaire par la conservation des gamètes. Depuis les congélateurs des centres de reproduction et des maternités, tous ces embryons congelés nous regardent et se demandent ce que l’on va faire d’eux.

“Mais quand on voit courir un enfant provenant d’un congélateur, on ne peut s’empêcher de penser à tous les embryons surnuméraires.”

Va-t-on les détruire, les conserver, les implanter ? Il y a aux États-Unis, a rappelé le professeur Ansermet, des associations, les « snow flakes » (flocons de neige), qui proposent à l’adoption des embryons congelés, faisant valoir leur droit à être utilisés une fois qu’ils ont été conçus. Mais quand on voit courir un enfant provenant d’un congélateur, on ne peut s’empêcher de penser à tous les embryons surnuméraires. Que vont-ils devenir ?

De même, pouvoir conserver les ovocytes implique l’idée qu’ils puissent être conservés plusieurs années avant d’être réimplantés une ou deux décennies plus tard, une fois achevée la brillante carrière professionnelle de leur « propriétaire ». Des disjonctions encore plus importantes vont apparaître, selon le professeur Ansermet, promises par l’intelligence artificielle et le transhumanisme, les cyborgs et robots, laissant entrevoir un re- tour à Pygmalion et Galatée: Pygmalion dit à Galatée: « Toi c’est moi, tout mon moi est en toi, je ne vis plus désormais qu’en toi. » Le transhumanisme met en évidence la difficile question des droits et des devoirs des robots. Voyons Sophia, le robot humanoïde mis au point par Hanson Robotics, conçu pour tout apprendre en s’habituant au comportement des êtres humains. Sophia est capable de répondre aux questions et a même été reçu à l’ONU. En octobre 2017, le robot a obtenu la nationalité saoudienne, faisant de lui le premier androïde au monde à recevoir la citoyenneté d’un pays.

En fin de compte, pour François Ansermet, les technologies de la procréation dévoilent un impossible à penser qui est source d’une angoisse éthique. Pensons par exemple à la procréation dans les couples de femmes, qui institutionnalise la fabrication d’un enfant sans père. Mais qu’est-ce qu’un père ? Un géniteur, un père au sens de la loi, un père d’intention, une simple figure masculine ? Et quel est le rôle de la différence des sexes dans le développement de l’enfant ? La gestation pour autrui rend la mère incertaine, a souligné le professeur Ansermet. Il y a celle qui a donné l’ovule et celle qui a donné le ventre. Et certains couples de femmes croisent le ventre et l’ovule. Dans le monde juridique, l’enfant appartient à la mère du ventre de laquelle il est sorti. Dans le monde génétique on a tendance à dire que ce sont les gamètes. L’irreprésentabilité de l’origine, l’irreprésentabilité du lien entre sexualité et procréation, l’irreprésentabilité de la mort dans la procréation donnent le vertige. Platon dans « Le banquet » fait parler Socrate qui rapporte les propos de Diotime que l’on peut résumer ainsi: la procréation vise la part d’immortel dans le vivant mortel. Vivre au-delà de soi par le fait de procréer.

Pour François Ansermet, ce que nous n’arrivons pas à penser est bouché par des constructions fantasmatiques, imaginaires. Mais le fantasme protège de l’angoisse autant qu’il le génère. Le fantasme permet d’imaginer de nouvelles biotechnologies qui vont introduire de nouveaux scénarios imaginaires. Effectivement ces biotechnologies viennent modifier la réalité. Il y a donc une spirale qui se crée entre biotechnologies, angoisse et réalité et cela ne peut que nous perturber. Ceci constitue une préoccupation majeure pour le clinicien, le pédopsychiatre qui se trouve face à ces tableaux. Il ne doit pas laisser voguer son imaginaire trop loin et plutôt se fier, au cas par cas, à ce que disent les sujets.

L’artiste Prune Nourry a créé à Genève un Dîner procréatif auquel François Ansermet a pris part. Les Dîners procréatifs sont des performances associant art, gastronomie et science. Prune Nourry s’associe à un chef et à un scientifique pour concevoir un repas qui suit les différentes étapes de la procréation assistée, faisant de la fécondation in vitro un cocktail et du choix du sexe de l’enfant un plat principal, invitant ainsi les participants à réfléchir au concept de « l’enfant à la carte ». Le Dîner procréatif soulève la problématique suivante: Les nouvelles techniques de procréation assistée nous mènent-elles vers une évolution artificielle de l’humain à travers la sélection ?

Au cours de ce dîner plutôt particulier (qui débute dans un sperme bar…), les convives reçoivent des embryons, l’un aveugle, l’autre trisomique, le troisième sourd, le quatrième porteur d’un risque d’Alzheimer, à choix. Tous ont donc des problèmes et l’idée est de mettre les participants face au vertige du choix prédictif.

D’où viennent les enfants ? À chacun son explication, à chacun sa représentation. Samuel Beckett dans « Fin de partie » fait dire à un fils devant son père: « Pourquoi tu m’as fait ? » « Je ne pouvais pas savoir », répond le père. « Quoi, qu’est-ce que tu ne pouvais pas savoir ? » « Je ne pouvais pas savoir que c’était toi ! » Pour François Ansermet, l’enfant est un chercheur de son origine.

D’où viennent les enfants ? Pour François Ansermet, fantasmatiquement, nous sommes tous issus d’une procréation médicalement assistée dans la mesure où, c’est d’ailleurs le paradoxe, certaines réactions affectives, en court-circuitant concrètement le sexe dans la procréation, révèlent la place de la sexualité dans celle-ci.

“Les marginaux de demain seront dès lors les hétérosexuels qui procréeront sans analyse du sperme, des risques génomiques et autres.”

Vertige de la différence. Un sujet d’actualité, a rappelé le professeur Ansermet. Couples de femmes, femmes seules, couples d’hommes, hommes seuls, transgenres, asexuels, tout ce petit monde peut avoir des enfants. Et cela peut donner lieu dans les médias à des dessins humoristiques ainsi légendés : « Va vivre chez ta mère porteuse ! Retourne dans ton utérus de location ! Va habiter chez ton donneur de sperme ! Prends les clés de ton éprouvette et dégage ! »

Vertige de la prédiction. Le troisième vertige aux yeux de François Ansermet. Un vertige qui s’inscrit surtout dans le cadre de la problématique des droits de l’enfant avec un lien possible entre procréation et prédiction de ce que l’enfant va être. Prédire s’il sera porteur d’une maladie génétique monogénique, s’il sera porteur de gènes dominants ou récessifs, s’il sera sujet à des maladies polygéniques. Pour le professeur Ansermet, nous entrons dans un nouveau monde qui posera la question du droit des enfants à supporter le hasard de leur procréation.

François Ansermet souhaite nous rendre attentifs au paradoxe suivant: actuellement, ce sont les marginaux – couples de femmes, femmes seules, couples d’hommes, hommes seuls – qui demandent telle ou telle chose en matière de procréation en fonction de leurs choix sexuels. Or ces demandes impliquent une technologisation de la procréation et banalisent sa médicalisation. Les marginaux de demain seront dès lors les hétérosexuels qui procréeront sans analyse du sperme, des risques génomiques et autres. Une transformation importante est en cours en matière de demandes sociétales. Quid dans le futur du droit à l’incertitude, du droit à ne pas savoir ?

La problématique est complexe comme celle par exemple des screenings pré-conceptionnels. Les généticiens pour leur part se déclarent en faveur des dia- gnostics pré-conceptionnels dans la mesure où ils permettent de protéger les enfants de maladies terribles comme l’hémophilie ou la mucoviscidose. On peut comprendre leur logique mais en même temps on peut se demander quel serait le destin de Roméo et Juliette à l’ère de la génomique. Peut-être que sur les sites de rencontre du web figurera un jour une rubrique sur la génomique des individus comme on y trouve aujourd’hui différents paramètres comme la taille de l’individu, la couleur de ses yeux, son niveau d’études et son parcours professionnel. La dimension est majeure : choisir entre le droit de savoir et celui de ne pas savoir. Pour François Ansermet, le fait de prédire peut conduire à une stratification, une ségrégation. Or le système de santé actuel est fondé sur la solidarité et la réciprocité, qui tient à un non-savoir. Il existe un paradoxe de la prédiction qu’il convient de rappeler: toute prédiction dévoile aussi l’infini de ce qui ne peut être prédit.

Quel devenir ? Pour le professeur Ansermet, il y en a un au-delà de la prédiction, au-delà de la procréation, c’est évident. Il est donc important de rappeler la place du devenir, de ne pas ramener l’enfant à ses conditions de procréation. Le droit des enfants est d’être considérés comme des enfants, et de ne pas être considérés en fonction de leur mode de procréation. Il faut éviter de faire de l’origine un destin. Et œuvrer cliniquement, socialement, politiquement. Dans la clinique, la procréation médicalement assistée peut fonctionner comme un piège de la causalité, causalité à tout faire et qu’on imagine comme une continuité. Si l’on veut réfléchir à l’éthique de la procréation médicalement assistée par rapport aux trois vertiges, François Ansermet pense qu’il conviendrait de constituer des assises du déterminisme et de réfléchir au statut et aux conceptions que nous avons du déterminisme. Sommes-nous capables d’être les auteurs et les acteurs de notre propre devenir ? Comme le lui disait une patiente atteinte d’une maladie génétique: avoir un enfant, est-ce quelque chose qui continue ou est-ce quelque chose de nouveau qui commence ? Une question merveilleuse.

Il y a une logique de continuité déterministe avec la question génomique, a relevé François Ansermet. Au fond, peut-être devrions-nous passer à une logique de la réponse, c’est-à-dire faciliter dans le travail clinique la réponse du sujet, celle de l’enfant et celle de ses parents. Réponse va avec responsabilité. Et de sa position chaque sujet est responsable. C’est tout l’enjeu de la clinique, peut-être l’enjeu du droit des enfants, l’enjeu des entreprises humanistes, de l’ONU, de la Commission des droits de l’enfant. Pour François Ansermet, l’enjeu, c’est d’ouvrir l’avenir, permettre à l’enfant d’être l’auteur et l’acteur de son propre devenir.

Paul Valéry a écrit: « Qu’est-ce que vous faites aujourd’hui ? Je m’invente. » Pour le professeur Ansermet, il y a toujours de la place pour l’invention et c’est cette place qui doit être défendue tant par les cliniciens que par ceux qui s’occupent du droit des enfants.

AD MAJOREM DEI GLORIAM | Printemps 2019

HAVING A BABY TOMORROW: THE CHALLENGES OF PROCREATION IN THE AGE OF BIOTECHNOLOGY

Advances in biotechnology make it possible to realize what was previously a fantasy, leading to multiple vertigo. Vertigo of origin: a child can be born from a sperm donation, an ovum donation, an embryo donation or a surrogate motherhood, thus creating new filiations. Vertigo of difference: through procreation in female couples or by single women, in male couples or by single men, or in transgender people. Vertigo of prediction: through a possible link between procreation and prediction, which could occupy more and more space in the era of genome sequencing.

These technological possibilities can fascinate as much as they can be a source of perplexity, even anxiety. But they can also surprise us by the new origins that they make possible from now on and that we have to accompany by dealing with a world that is sometimes invented faster than our capacity to follow it.

It was on this theme that François Ansermet, honorary professor at the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and the University of Lausanne (UNIL), spoke in Sion, Valais, in September 2018, after having been first ordinary professor of child psychiatry, vice-dean of the Faculty of Biology and Medicine at UNIL, Chief of the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Service at the University Hospital of Vaud (CHUV), then full professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the University Hospital of Geneva (UNIGE) and, at the hospital level, Chief of the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Service at the University Hospital of Geneva (HUG), as well as Director of the University Department of Psychiatry at the Faculty of Medicine of the UNIGE.

of Medicine of the UNIGE. In addition, François Ansermet has been a member of the National Consultative Ethics Committee in Paris since 2013.

For François Ansermet, the rights of the child are today at the center of the concerns of child and adolescent psychiatry. Childhood builds the world of tomorrow. But will it be possible to be a child tomorrow in the world as it is evolving? It is the great question that the professor asks. Marriage for all, in a certain number of countries for example, has led to the question of procreation for all, which raises important resistances, just like the problems of genomics and artificial intelligence.

“Childhood builds the world of tomorrow. But will it be possible to be a child tomorrow in the world as it is evolving?“

All these themes, Professor Ansermet noted, are the subject of collective stances, including from religious circles. The cursor of the symbolic runs faster than we do, which for all that should not be interpreted as a crisis. Resistance to the new is understandable and we must recognize that this new exists and that childhood is watching us.

Biotechnology implies new modes of procreation. It is a question of creating life in a world that also creates death — through wars, crimes, racism. We must not fall into catastrophism, warned Professor Ansermet who recalled the importance of myths and religions that have always thematized the creation of life. Long before medically assisted procreation, there were divinely assisted procreations, well beyond the biological. In “The Golden Legend” of James of Voragine, during the Renaissance — a work that inspired the painters of the quattrocento — it is said that God can create man in four ways: without man or woman, as he did for Adam; by man without woman, as he did for Eve; by woman without man, as happened miraculously following the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary, which is first of all the feast of the Incarnation since God begins in Mary his human life that will lead Jesus to the Cross and the Resurrection, to the Glory of God — see Dante’s “The Divine Comedy”: “O Virgin Mother, Daughter of Your Son”. With biotechnologies, Professor Ansermet emphasized, we are well below what the human imagination has been able to construct on the mystery of origin, on the mystery of coming into the world. Finally, the fourth mode of creation of the man evoked in ” The golden Legend ” is ” by the man and the woman according to the common way “. Among the myths having for subject the creation of the life, one can quote Athena going out, all armed, of the head of Jupiter and Dionysos born twice, of the belly of Sémélé and the thigh of Jupiter.

The world of procreation is changing faster than our ability to keep up with it, observed François Ansermet. So what are these biotechnologies that are turning our minds upside down? It is true that these biotechnologies and their impacts are the object, with good reason, of a certain perplexity on the part of the public. Far from the romantic vision of science whose advances allow the conception and the implementation of new medical treatments, it is appropriate to question today these technologies of procreation which operate on the world without us knowing exactly what they are about. It can indeed be extremely worrying to think that we have techniques operating on reality and at the same time not know what product will come out of it. These technological approaches can lead to non-knowledge. The result is a manufactured, invented, new world, which we do not know what it is. This is the reason why the questions resulting from the current technological discoveries are more and more treated within ethics committees, real observatories of the contemporary perplexity and anguish, that is to say observatories of what we cannot represent.

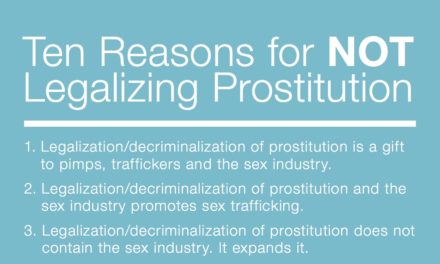

Image

Press conference for the birth of the first test-tube baby in France with professors René Frydman, Emile Papiernik and Jacques Testard, April 10, 1986 in Clamart, France

For François Ansermet, in front of the unrepresentable, in front of what leaves perplexed and anguished, two types of reaction are possible. On the one hand, the techno-prophets announce a new world in which it will be possible to procreate even if one is infertile and to select children who will not suffer from diseases. They promise us a better world. On the other hand, there are the bio-catastrophists who argue that if we touch nature, we touch the law, with the idea of a superposition of the natural law and the moral law. There would thus be transgression of nature by means of these technologies. For the clinician, the stake is indeed to be at the height of the time that we live. It is advisable, according to him, not to be locked up in a conservative temptation and not to curse his time. We must deliberately look to the future rather than cling to the past. On the one hand, not to fear uncertainty and, on the other, not to succumb to the tyranny of the past. And to be able to situate oneself in these two dimensions.

The new modes of medically assisted procreation such as in vitro fertilization, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, oocyte conservation, pre-implantation and pre-conceptional diagnosis, posthumous procreation and others are surprising, disturbing, upsetting and producing a vertigo. For François An- sermet, a vertigo that both anguishes and attracts, a vertigo that is a source of fascination. The media do not hesitate to tell us in detail about cases of assisted procreation that are totally astounding. Nothing surprising in that since they titillate a cord which is particularly sensitive to all of us, that of our origin which goes hand in hand with Sexuality with a capital S — the big word that moves is released.

“And it is indeed the question that all children ask: why am I me and not someone else?“

Where does this vertigo come from, or rather these vertigoes? For François Ansermet, there are three: the vertigo of origin, the vertigo of the difference of the sexes in procreation and that of prediction. Regarding the first, the vertigo of origin, Professor Ansermet wishes to recall that the world of origin, symbolic and

of origin, symbolic and imaginary, is different from the world of sexuality. The problem lies in the fact that we live in an era of very biological paradigms and that we tend to think that origin is equal to sexuality, that procreation is equal to gestation, that birth is equal to filiation, whereas all these worlds are disjointed. The most unrepresentable of this series is certainly procreation. When does it occur? What is its moment M? When is life created? Even biologists working in assisted reproduction centers are very hesitant about the question of the emergence of life, namely when cells combine and then come to multiply. Where does this spark come from? For François Ansermet, the fundamental question on which everyone stumbles, including biologists and doctors of reproduction, is the following: where do children come from? Freud considered this to be the impossible question par excellence. And it is indeed the question that all children ask: why am I me and not someone else? Why here rather than elsewhere? François Ansermet liked to quote the story of a little girl of 8 whose mother is pregnant. At breakfast, the mother makes a honeyed sandwich for her daughter. The latter looks at her mother’s belly and asks her what “that” is. The mother replies that she is expecting a new child. “Where does this child come from?” asks the child. The mother tries to explain: the father and mother, the kiss, the little seed. “When you see this honey on this toast, think of the bees, the flowers, the pollen…” The little girl then cut her mom off: “Stop with these completely lame explanations. At school we’ve already had sex education classes, we know exactly what it’s all about. I’m not asking you what position you and daddy took to have this new child.”

Image

Photo Vincent Migeat/Agence VU

The mother sweats, the drops of sweat fall on the honey toast. “What do you want to know, finally?

the mother. And the little girl answers very firmly: “Before being in your belly, where was I?” For Professor Ansermet, the beauty of this question is a wonder: “It’s like a dead man, we say his body is in the earth, his soul is in heaven; children say: OK. But when I am dead, when my body is on earth, when my soul is in heaven, where will I be?

For François Ansermet, the major problem posed by medically assisted reproduction technologies is that they are sources of disjunction. Sexuality is separated from procreation, procreation from gestation, gestation from birth — it is possible to go through surrogate motherhood with a surrogate mother — and finally, the origin of filiation is separated — by donations of sperm, ova, embryos, double donations and, should we add, creating a temporary disjunction by the conservation of gametes. From the freezers of the reproduction centers and maternity wards, all these frozen embryos look at us and wonder what we will do with them.

“But when you see a child running from a freezer, you can’t help but think of all the supernumerary embryos.“

Are we going to destroy them, preserve them, implant them? In the United States, Professor Ansermet recalled, there are associations, the “snow flakes”, which propose frozen embryos for adoption, asserting their right to be used once they have been conceived. But when you see a child running from a freezer, you can’t help but think of all the surplus embryos. What will happen to them?

Likewise, being able to store oocytes implies the idea that they can be stored for several years before being re-implanted a decade or two later, once the brilliant professional career of their “owner” is over. Even more important disjunctions will appear, according to Professor Ansermet, promised by artificial intelligence and transhumanism, cyborgs and robots, suggesting a re-turn to Pygmalion and Galatea: Pygmalion says to Galatea: “You are me, all my self is in you, I live only in you. Transhumanism highlights the difficult question of the rights and duties of robots. Let’s take a look at Sophia, the humanoid robot developed by Hanson Robotics, designed to learn everything by getting used to the behavior of human beings. Sophia is able to answer questions and has even been received at the UN. In October 2017, the robot was granted Saudi citizenship, making it the first android in the world to receive citizenship of a country.

Ultimately, for François Ansermet, reproductive technologies reveal an impossible to think about that is a source of ethical angst. Let us think for example of procreation in couples of women, which institutionalizes the fabrication of a child without a father. But what is a father? Is he a father, a father in the sense of the law, a father of intention, a simple male figure? And what is the role of gender difference in the development of the child? Surrogate motherhood makes the mother uncertain, Professor Ansermet pointed out. There is the one who gave the ovum and the one who gave the womb. And some couples of women cross the womb and the ovum. In the legal world, the child belongs to the mother from whose womb it came. In the genetic world we tend to say that it is the gametes. The unrepresentability of the origin, the unrepresentability of the link between sexuality and procreation, the unrepresentability of death in procreation make one dizzy. Plato in “The Banquet” makes Socrates speak and he reports Diotime’s words which can be summarized as follows: procreation aims at the part of the immortal in the living mortal. To live beyond oneself by procreating.

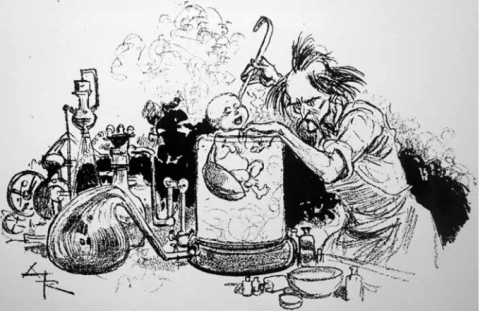

Image

Cartoon illustrating the creation of a test-tube baby, by Albert Robida (1848–1926), French cartoonist and novelist. Dated from the 19th century. Photo: Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images

For François Ansermet, what we cannot think is blocked by phantasmatic, imaginary constructions. But the fantasy protects from anguish as much as it generates it. The fantasy allows us to imagine new biotechnologies that will introduce new imaginary scenarios. Indeed, these biotechnologies modify reality. There is thus a spiral that is created between biotechnologies, anxiety and reality and this can only disturb us. This constitutes a major concern for the clinician, the child psychiatrist who is confronted with these pictures. He must not let his imagination wander too far and rather rely, on a case by case basis, on what the subjects say.

The artist Prune Nourry created a Procreative Dinner in Geneva in which François Ansermet took part. The Procreative Dinners are performances combining art, gastronomy and science. Prune Nourry joins forces with a chef and a scientist to create a meal that follows the different stages of assisted reproduction, making in vitro fertilization a cocktail and the choice of the child’s sex a main course, thus inviting participants to reflect on the concept of the “à la carte child”. The Procreative Dinner raises the following issue: Are the new assisted reproduction techniques leading us towards an artificial evolution of humans through selection?

During this rather peculiar dinner (which starts in a sperm bar…), the guests are given embryos, one blind, one with Down’s syndrome, one deaf, one with Alzheimer’s risk, to choose from. All of them have problems and the idea is to put the participants in front of the vertigo of predictive choice.

Where do the children come from? To each his explanation, to each his representation. Samuel Beckett in “Endgame” has a son say to his father, “Why did you make me?” “I couldn’t know,” replies the father. “What, what couldn’t you know?” “I couldn’t know it was you!” For François Ansermet, the child is a researcher of his origin.

Where do children come from? For François Ansermet, phantasmatically, we all come from a medically assisted procreation insofar as, it is besides the paradox, certain affective reactions, by concretely short-circuiting the sex in the procreation, reveal the place of the sexuality in this one.

“The marginalized of tomorrow will therefore be the heterosexuals who procreate without analysis of sperm, genomic risks and others.

Vertigo of the difference. A topical subject, reminded Professor Ansermet. Female couples, single women, male couples, single men, transgender, asexual, all this little world can have children. And that can give place in the media to cartoons thus captioned: “Go live with your surrogate mother! Go back to your rented womb! Go live with your sperm donor! Take the keys to your test tube and get out!”

Vertigo of the prediction. The third vertigo in the eyes of François Ansermet. A vertigo which is especially in line with the problem of the rights of the child with a possible link between procreation and prediction of what the child will be. Predicting whether he will be a carrier of a monogenic genetic disease, whether he will be a carrier of dominant or recessive genes, whether he will be subject to polygenic diseases. For Professor Ansermet, we are entering a new world which will raise the question of the right of children to bear the chance of their procreation.

François Ansermet wishes to make us aware of the following paradox: currently, it is the marginalized — female couples, single women, male couples, single men — who ask for this or that thing in terms of procreation according to their sexual choices. But these demands imply a technologization of procreation and trivialize its medicalization. The marginalized of tomorrow will therefore be heterosexuals who will procreate without sperm analysis, genomic risks and so on. An important transformation is underway in terms of societal demands. What about the future right to uncertainty, the right not to know?

The issue is complex, as is the case with pre-conceptional screenings, for example. Geneticists, for their part, declare themselves in favour of pre-conceptional dia- gnostics insofar as they make it possible to protect children from terrible diseases such as haemophilia or mucoviscidosis. One can understand their logic but at the same time one can wonder what would be the fate of Romeo and Juliet in the era of genomics. Maybe one day, on the dating sites of the web, there will be a section on the genomics of individuals, as there are today different parameters such as the height of the individual, the color of his eyes, his level of education and his professional background. The dimension is major: choosing between the right to know and the right not to know. For François Ansermet, the fact of predicting can lead to stratification and segregation. Yet the current health system is based on solidarity and reciprocity, which is based on not knowing. There is a paradox of prediction that should be remembered: any prediction also reveals the infinity of what cannot be predicted.

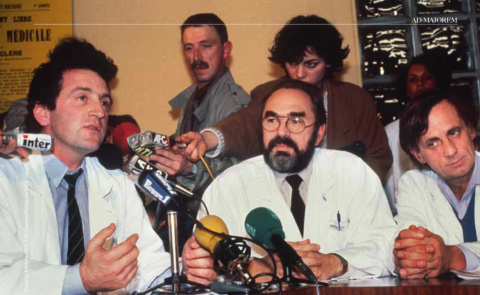

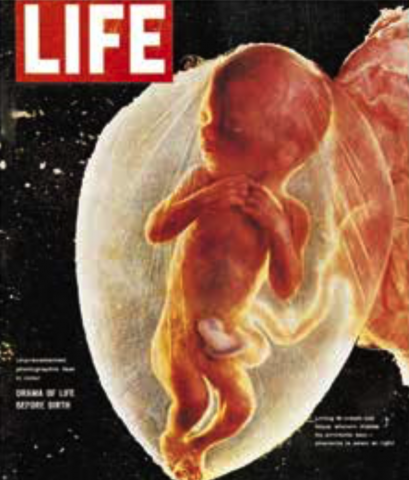

Image

First photo of a human fetus published in the press (Cover of Life, 1965, photo by Lennart Nilsson). Photo 12 / UIG via Getty Images

What will become of it? For Professor Ansermet, there is one beyond prediction, beyond procreation, that is obvious. It is therefore important to recall the place of becoming, not to reduce the child to its conditions of procreation. The right of children is to be considered as children, and not to be considered according to their mode of procreation. We must avoid making origin a destiny. And work clinically, socially and politically. In the clinic, medically assisted procreation can function as a trap of causality, an all-purpose causality that we imagine as a continuity. If we want to reflect on the ethics of medically assisted procreation in relation to the three vertigoes, François Ansermet thinks that it would be appropriate to constitute the foundations of determinism and to reflect on the status and conceptions that we have of determinism. Are we capable of being the authors and actors of our own future? As a patient with a genetic disease said to her: is having a child something that continues or is it something new that begins? A wonderful question.

There is a logic of deterministic continuity with the genomic question, noted François Ansermet. Basically, perhaps we should move to a logic of response, that is to say, to facilitate in the clinical work the response of the subject, that of the child and that of his parents. Response goes with responsibility. And each subject is responsible for his position. This is what is at stake in the clinic, perhaps what is at stake in children’s rights, what is at stake in humanist enterprises, in the UN, in the Commission on the Rights of the Child. For François Ansermet, the challenge is to open up the future, to allow the child to be the author and actor of his own future.

Paul Valéry wrote: “What are you doing today? I am inventing myself.” For Professor Ansermet, there is always room for invention, and it is this room that must be defended by both clinicians and those involved in children’s rights.

AD MAJOREM DEI GLORIAM | Spring 2019