Please watch the video of this event and read the full text of the interventions below the programme:

RIGHT TO LIFE AND HUMAN DIGNITY

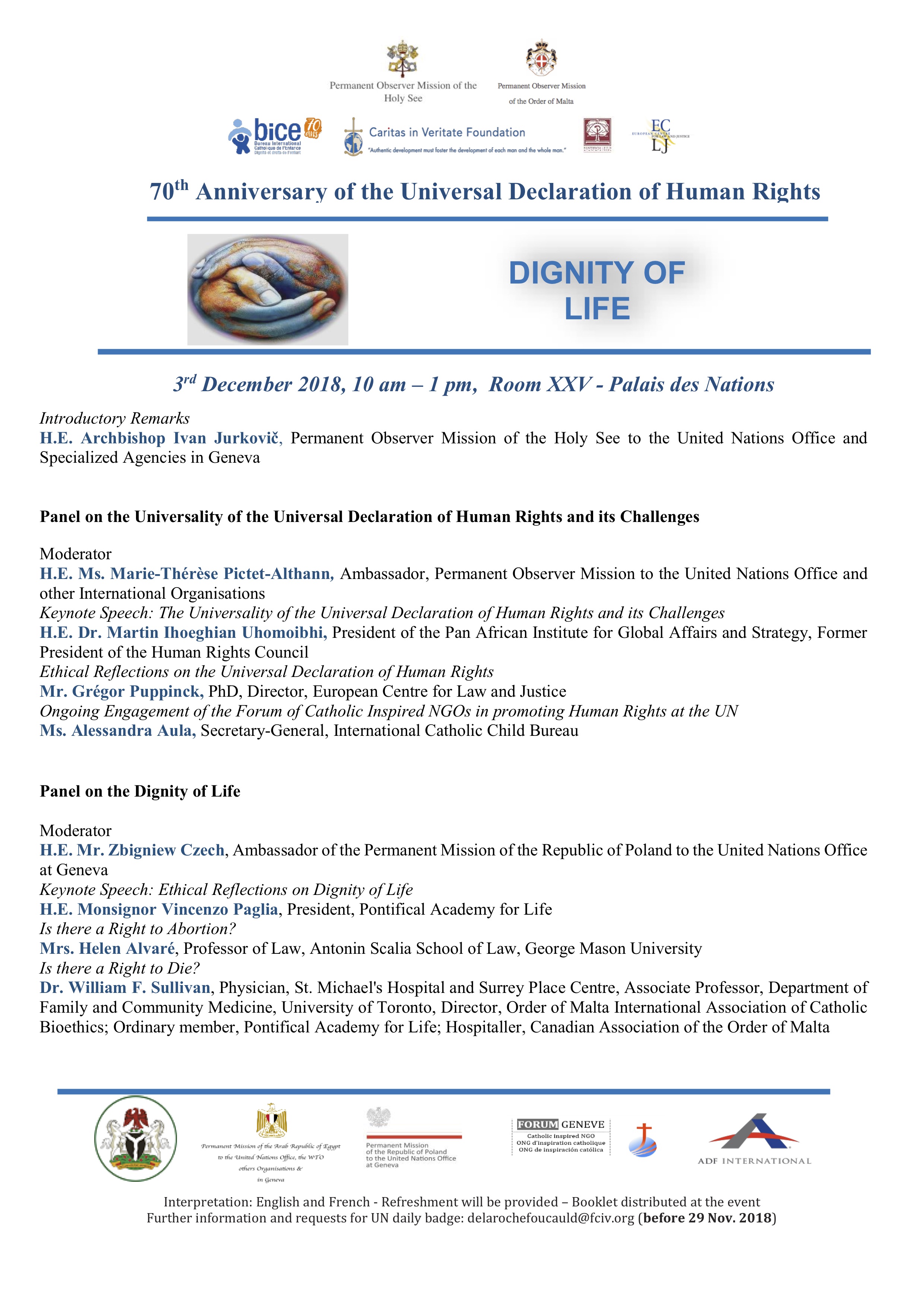

70th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Texts of the presentations on the 3rd of December 2018 in Geneva at the Palais des Nations

EDITORIAL

ARCHBISHOP IVAN JURKOVIČ

Permanent Observer of the Holy See to the United Nations and other International Organizations in Geneva

“The General Assembly, proclaims this Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction.”’ Seventy years ago, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) stated, for the first time in the history of modern States, the primacy of freedom and the unity of the human family over and above any political or ideological divisions based on race, sex, religion or any other human characteristic. The objective was to defend the individual from the absolute prominence of the State, which totalitarian ideologies might “divinise” and thus promote as an alternative way to build the “city of man”. The UDHR represented a new attempt to eradicate the elements allowing violence and genocide in the past World Wars and to affirm the importance and centrality of the human being in the relations between States and the International Community, all with the aim to build a new and more peaceful future. To achieve this ambitious goal, the Declaration recognised the natural rights of every individual, affirming the primacy of life, the importance of social community, and the need to build structures capable of guaranteeing democracy, rule of law, and accountability. The Declaration was not only a simple proclamation but a new stance taken by the International Community as a whole, and it aimed to place human dignity among the highest values which organise the internal and external behaviour of nations, societies, and governments. This stance is still valid today; more importantly, it cannot be substituted because it is the only approach that elevates the individual as the primary actor and recipient of all political decision while simultaneously evaluating the social implications of the rights shared among all human beings. With great respect, the Holy See recognises “all the true, good and just elements inherent in the very wide variety of institutions which the human race has established for itself and constantly continues to establish’7 Therefore, it has always considered this Declaration as ‘a step in the right direction, an approach toward the establishment of a juridical and political ordering of the world community’? The Declaration represents a very precious reference point for cross- cultural discussion of human dignity and freedom in the world. The quotation shared at the opening of this article concludes the UDHR Preamble and establishes the goal of this document, which is now shared by nine additional human rights treaties elaborated in the past seventy years following the Declaration. In the present era, the international context has changed radically, and the entire structure of the human rights doctrine and law is struggling to confront new theoretical and practical threats. On one hand, the consensus that approved the Declaration and reaffirmed it through the adoption of the Vienna Declaration and the related Programme of Action twenty-five years ago, seems to be weakened; meanwhile, different conceptions, and even denunciations of human rights as a mere product of Western culture, are gaining ground in different international and regional fora. On the other hand, recent decades have witnessed the birth of the category of so— called “new rights”, emerging from a theoretical approach that fragments the human being and promotes a selective and often conflicting concept of individual freedom. These different stances lead to misperceptions and confusion that undermine the global recognition of human rights as universal in their nature, thus risking trivializing “one of the highest expressions of the human conscience of our time”.’ In its actions at the United Nations, as well as in all its international positions, the Holy See has always supported the implementation of this important Declaration and consistently reaffirms that we share a common human dignity—dignity which provides the indispensable background that sustains the interrelatedness, universality, and indivisibility of human rights. As Pope Francis posited during an address to the diplomatic corps accredited to the Holy See: ‘From a Christian perspective, there is a significant relation between the Gospel message and the recognition of human rights in the spirit of those who drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.’^ Indeed, it is this ‘spirit’ that we have to recover and re-propose to the world and to every human being, by emphasizing that ‘recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world’. The aim of this booklet is to present certain aspects of the Holy See’s position and reemphasize the original intent of the Declaration. This requires, for instance, clarification on why the right to life is ‘the supreme right from which no derogation is permitted’^ and has crucial importance both for individuals and for society as a whole. The effective protection of the right to life is the prerequisite for the enjoyment of all other human rights. Therefore, the right to life requires a commitment to uphold life from conception to natural death. In all its interventions at the United Nation and other international organizations, the Holy See upholds the original ideals of the U.N. Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, maintaining the anthropological conception of the human being as an individual in constructive relation with other human beings, all sharing the same equal dignity from conception to natural death. The drafters of the UDHR knew that the success of their effort would require developing, over time, a ‘common understanding’ of the meaning of the document—as the Preamble states explicitly. Moreover, the development of the vocabulary of human rights profoundly influenced the effective implementation of the UDHR over the next decades. The attempts to rewrite the profound meaning of human rights a posteriori have often brought less clarity and conflict, weakening the same structure that was intended to reinvigorate and expand. In fact, the unilateral affirmation of ‘new rights’, based on certain theoretical and anthropological views, has favoured those who blame the entire structure of human rights as being influenced by Western culture or, even worse, as a new kind of culture colonisation. However, these accusations fail to understand that the UDHR was ‘the outcome of a convergence of different religious and cultural traditions, all of them motivated by the common desire to place the human person at the heart of institutions, laws and the workings of society’ rather than the imposition of one culture on all others. In the political vocabulary of human rights today, even a minimal agreement on the core meaning of human dignity is rapidly disappearing and becoming fragmented into incoherence. In the ‘politics’ of human rights, dignity is invoked for the most disparate and contradictory ideas, so much so that it is essentially impoverished of its meaning in some human rights discourse and deconstructed into different, often conflicting, parts. Human dignity is frequently used to justify many so-called ‘new rights’, even those which contradict or deny the very origin of their basis, which are extensively and expertly presented in the contributions to this booklet. The illustrations of the deconstruction and reinterpretation of dignity are numerous, but in the interest of brevity, I will cite only one prominent example, namely the political efforts in many constitutional and international contexts aimed at legalizing physician-assisted suicide and more active forms of euthanasia; they have taken the word ‘dignity’ as their rallying cry—‘death with dignity.’ Consequently, dignity has become something that is achieved through a problematic act of will rather than something inherent in the person that is inviolable and worthy of respect. If we want to reinvigorate the human rights structure, favouring the global implementation of the Universal Declaration and safeguarding the concept of universality that is at the core of the Declaration, we should abandon those interpretations of rights that are objectively distant from the founding texts and thus contribute to making universal consensus much more difficult. If we fail to do this, we risk creating a ‘conflict of anthropologies’, which has already intensified by the process of globalization and human mobility.® It is important to clarify that the rights recognized by the UDHR were not intended to be reinterpreted or reshaped according to the political or social tendencies of the moment. Indeed, they are derived from the human dignity that is common, shared, and inherent to every human being, regardless of any other difference. The Preamble of the UDHR concludes with clear and well-defined objectives, simultaneously identifying every human being and institution as an active participant in the implementation and expansion of human rights—rights which ultimately aim to ‘secure their universal and effective recognition’?® The following articles within the booklet encompass contributions of different authors and of the Holy See, all committed to the common effort of the International Community to build a better world where “the universality, indivisibility and interdependence of human rights all serve as guarantees safeguarding human dignity”.’ Facing the challenges and conflicts of our time, we should recognize that due respect of human rights is the true source of peace. Today, the multilateral system is blocked and encounters enormous difficulties; in the meantime, many international organizations are struggling against a growing lack of legitimacy. In this regard, the 70th Anniversary of the UDHR can be a turning point. Though directly referring to a previous economic crisis. Pope Benedict XVI’s encouraging words from his Encyclical Letter Caritas in Veritate hold wisdom for us today, especially in our struggle to recognize basic human truths: ‘The current crisis obliges us to re-plan our journey, […] to discover new forms of commitment, to build on positive experiences and to reject negative ones. The crisis thus becomes an opportunity for discernment, in which to shape a new vision for the future’.^^ This Anniversary represents a unique opportunity to reaffirm the UDHR’s pivotal importance as a reference point for global and cross-cultural discussion on human rights, freedom, and dignity. It represents further opportunity to restate those very concepts of human rights, democracy, rule of law, and individual freedom that have their roots in the recognition and promotion of human dignity. The relevantwork of the United Nations should serve as a base and building-block on which to acknowledge this transcendent dignity and in order to fulfil the hope that ‘this Institution, all its member States, and each of its officials, will always render an effective service to mankind, a service respectful of diversity and capable of bringing out, for the sake of the common good, the best in each people and in every individual’.”

Geneva, December 2018