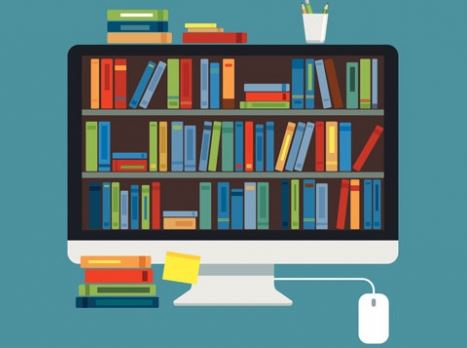

Exclusive interview with the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls, its causes and consequences, Mrs Reem Alsalem

This interview led by Grégor Puppinck, ECLJ Director, is focused on her report: Prostitution and violence against women and girls (A/HRC/56/48 — 7 May 2024)

Video excerpt:

Reem Alsalem: Pornography is filmed prostitution, and in my report I demonstrated that prostitution is a system of exploitation and violence against women and girls: it is very gendered, it predominantly affects females, and it is perpetrated by males.

Pornography operates in the same way; it has the same modus operandi, the same perpetrators of violence, the same exploitation, and the same consequences in terms of all forms of violence inflicted on women and girls—in terms of being exploited by pimps. Being a victim is not something undignified; on the contrary, being a victim is a legal term that means you have been subjected to gross violations of human rights, and you are entitled to assistance, protection, and reparations.

So, this is why I say they are victims—that they have, we have, an obligation, and states have an obligation to assist.

Grégor Puppinck: So, Madame Reem Alsalem, welcome to Strasbourg. Thank you. We are very pleased to welcome you here at the Europe Center for Justice in Strasbourg. It’s a great and a real pleasure and honor to have you with us. You are the current UN Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women and Girls since 2020. You are from Jordan, and you are most often traveling, often in Geneva at the United Nations. You have a mandate given by the Human Rights Council, which is a body of states in charge of human rights based in Geneva, depending on the United Nations. So, you are part of the UN human rights system and are the UN expert on violence against women and girls.

Thank you very much. It’s a very important topic. Currently, it’s also an important topic for our organization. You have published recently reports on various issues, including the matter of prostitution; you’re also working on pornography, issues of dignity, human trafficking against women, especially.

We would like to first give you the possibility to explain to the people what this date is, what its purpose is, and more importantly, why do you choose to address such difficult questions as pornography and prostitution?

Reem Alsalem: Well, first of all, thank you very much for having me. This is my first time in Strasbourg, which I regret—I should have come a long time ago because, of course, the Council of Europe and, in particular, the body that monitors the implementation of the Istanbul Convention, is a very important partner. Of course, I also follow very much what the European Court of Human Rights says, but also the Assembly, the Parliamentary Assembly, the debates, and the policies. So, really, a pleasure to be here.

The Human Rights Council of the United Nations is like the kitchen where human rights policy gets cooked. It was preceded by the Human Rights Commission, which is the one actually that created my mandate. My mandate is very old—last year, we celebrated 30 years of the mandate. It is actually one of the oldest special procedures that exist.

I’m not a staff member, actually, of the United Nations. A lot of people misunderstand that—they think I’m an official who has a paid salary that reports to our Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres, of the United Nations. But that is not the case. I’m an independent expert, appointed by the Council by virtue of my expertise to work on issues of preventing violence against women and girls. The mandate, for perhaps the longest time, was violence against women, and I believe two years ago, the mandate was expanded to include also violence against girls.

And that is something I requested because we always speak about a continuum of violence—that violence against women, particularly structural violence, misogyny, and harmful social norms, does not start affecting females when they become adults. Yes, they often start from sometimes from birth, sometimes even before birth, and into adulthood.

So I have a very big portfolio, which is to work with all stakeholders, but particularly states, in order to prevent violence. As you know, violence has reached epidemic levels. This has been acknowledged, of course, and it’s been exacerbated by many crises we’ve seen, especially in the last decade. We’ve seen an escalation of humanitarian crises, climate change, austerity measures, and economic hardship. And how states are also, let’s say, reducing budgets and attention dedicated to vulnerable groups, including women and victims of violence in general.

The needs are increasing, but resources are decreasing. So I do my work through various ways: I write thematic reports (you referred to one of them—we’re going to speak about it now). I also write letters to governments, but also non-state actors, businesses, military groups, on behalf of victims of suffering violence. I remind these stakeholders of their human rights obligations. These letters become public—they are published. If we receive a response, that response is also published, so anyone anywhere in the world can see the feedback we received.