SIDE EVENT AT UNITED NATIONS GENEVA

4 JULY 2023

NON-PUNISHMENT OF VICTIMS OF HUMAN TRAFFICKING:

ENHANCING PROTECTION OF VICTIMS

TEXTS OF INTERVENTIONS

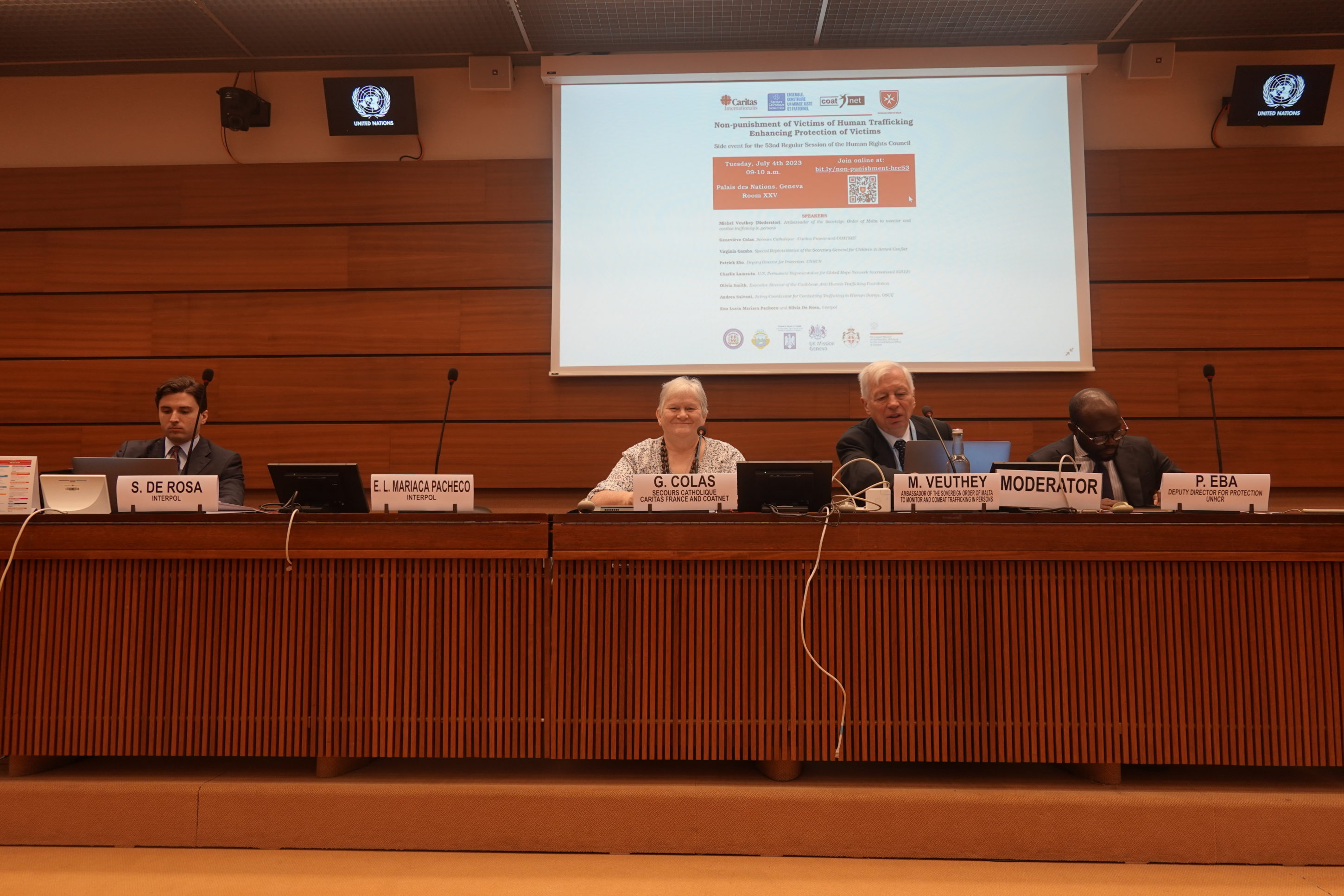

On July 4th, 2023, from 9 to 10 a. m., a side-event to the 53rd Session of the United Nation Human Right Council took place at the Palais des Nations in Geneva. The event was organized by the Sovereign Order of Malta in collaboration with Caritas Internationalis and Caritas France and the title was “Non-punishment of Victims of Human Trafficking: Enhancing Protection of Victims”.

Several Permanent Missions to the United Nations co-sponsored the event: Costa Rica, Poland, Romania, Sovereign Order of Malta, Great Britain, Dominican Republic.

As we know Human trafficking is a grave violation of human rights, affecting more then 50 million of individuals worldwide. Victims of human trafficking often face multiple forms of abuse, exploitation, and trauma. It is crucial to establish a comprehensive framework that not only supports victims but also prevents their punishment or criminalization for the crimes they were forced to commit. Twenty-three years after the Palermo Protocol (United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women, and Children), the scourge of human trafficking is far from being defeated.

This event hosted several professionals who discussed the topic from different aspects:

- Michel Veuthey (Moderator), Ambassador of the Sovereign Order of Malta to monitor and combat trafficking in persons

- Geneviève Colas, Secours Catholique — Caritas France and COATNET

- Virginia Gamba,Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children in Armed Conflict

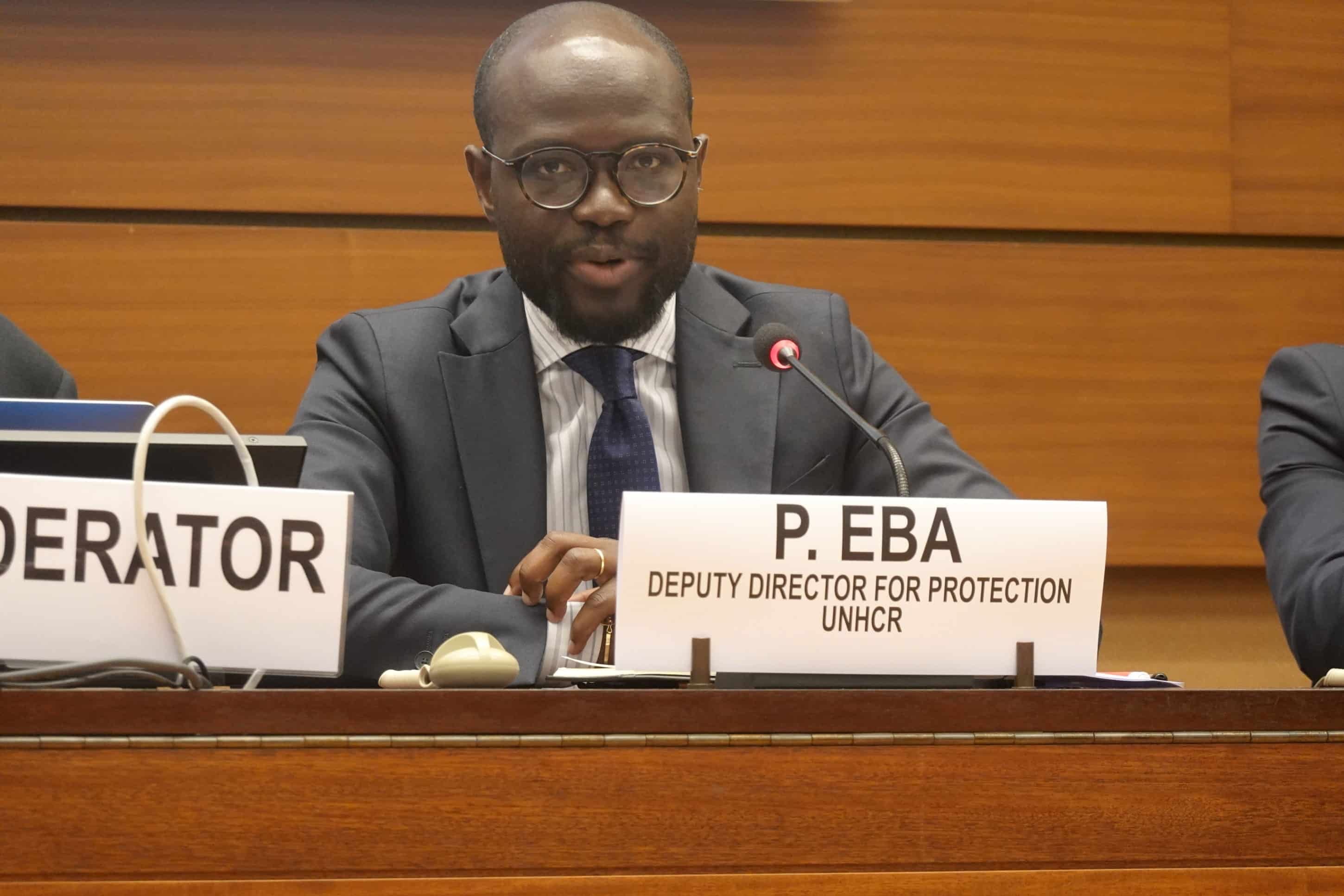

- Patrick Eba,Deputy Director for Protection, UNHCR

- Charlie Lamento,N. Permanent Representative for Global Hope Network International (GILLP)

- Olivia Smith,Executive Director of the Caribbean Anti Human Trafficking Foundation

- Andrea Salvoni,Acting Coordinator for Combatting Trafficking in Human Beings, OSCE

- Ena Lucia Mariaca Pachecoand Silvia De Rosa, Interpol

Michel Veuthey

Excellencies, Distinguished panelists, Ladies and Gentlemen, Good morning, everyone,

First of all, I would like to express my gratitude to Caritas Internationalis and all the Permanent Missions that have provided us with their support, in organising this side-event. I will keep my remarks brief.

The Sovereign Order of Malta is committed to upholding the principle of non-punishment of victims of human trafficking.

The Special Rapporteur Prof. Siobhán Mullally emphasized the importance of the non-punishment principle, which was the core of her report to her Human Rights Council in June 2021 (A/HRC/47/34) and was reaffirmed in her latest Report (A/HRC/53/28, Part XI. The Principle of Non-Punishment, paragr. 41–45).

So rather than detaining and punishing victims of trafficking, that we provide them with protection, identify them as victims, and seek to combat the ongoing impunity for trafficking.

I would now like to give the floor to our first speaker, Geneviève Colas, Secours Catholique France, co-organiser of this side-event. Geneviève, you have the floor!

Geneviève Colas

Enhance the protection of victims of human trafficking

by applying the principle of non-punishment

Geneviève Colas, Secours Catholique-Caritas France and COATNET global network

1/ In a rights-based approach, strengthening the protection of victims is a necessity

Victims of trafficking are often confronted with multiple forms of abuse and exploitation, all together creating trauma. It is essential to establish a global framework that supports victims while preventing them from being punished or criminalised for the crimes they have been forced to commit. Twenty-three years after the Palermo Protocol, victims of trafficking are still all too often held responsible for the unlawful activities they have committed in the course of their victimization. They are also held liable for accessory or consecutive acts: immigration/asylum, administrative or civil offences. Victims of trafficking are often arrested, charged, prosecuted and wrongly convicted for crimes and other illegal acts committed as victims of trafficking… while traffickers escape punishment and continue to engage in trafficking activities with impunity. This is a flagrant violation of victims’ right to protection.

The principle of non-punishment is therefore an essential element in the protection of victims of human trafficking and the prevention of their further victimisation. By recognising the vulnerability of victims, encouraging reporting, promoting rehabilitation and putting in place comprehensive support systems, societies can ensure that victims receive the protection and assistance they need to rebuild their lives. Non-punishment policies prioritise the rehabilitation of victims, giving them access to essential services such as healthcare, counselling, education and vocational training, enabling them to rebuild their lives.

2/ A few references on the non-punishment provisions contained in several international and regional anti-trafficking instruments

In 2002, in its resolution 55/67, the United Nations General Assembly invited governments to consider preventing victims of trafficking from being prosecuted for their irregular entry or residence within the legal framework and in accordance with national policies, given that they are victims of exploitation. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights recognised for the first time that trafficking in persons could be aimed at exploiting victims by making them carry out illegal activities. It already indicated that victims should therefore benefit from protection and not punishment for acts directly resulting from their status as victims of human trafficking.

In 2005, Article 26 of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings was the first treaty to contain a legally binding non-punishment provision.

In 2011, Directive 2011/36/EU on trafficking in human beings specifically recognises the growing phenomenon whereby traffickers coerce victims to forced criminality. It refers to this as one of the forms of exploitation included in the definition of trafficking in human beings. This directive contains an express binding provision on non-punishment (art 8). No limit is set on the seriousness of the offence.

In 2013, the OSCE pointed out the need for a comprehensive approach to combating human trafficking in order to implement the non-punishment provision for victims of trafficking. The more traffickers can rely on a State’s criminal justice system to arrest, charge, prosecute and convict victims of trafficking, instead of traffickers, for trafficking-related offences, the more favourable the conditions are for traffickers to take advantage and continue unhindered in their unlawful activity and undetected by the authorities.

In 2014, the ILO Protocol to the Forced Labour Convention included a provision for States to ensure that the competent authorities are empowered not to prosecute or impose penalties on victims of forced or compulsory labour.

In her 2015 report, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Trafficking in Human Beings states that States must protect victims of trafficking so that they are not held responsible for any illegal acts committed as a result of their submission to the dominant influence of their trafficker.

In her 2023 report on the protection of refugees, internally displaced persons and stateless persons, the Special Rapporteur, Ms Siobhán Mullally, emphasises, building on her 2021 report on the principle of non-punishment, that the State has an obligation to ensure that victims of trafficking have an effective opportunity to seek asylum and are not penalised because of the way in which they enter the country. The principle of non-punishment is also included in the specific protection afforded by Article 31 of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, which protects refugees from punishment for illegal entry and presence.

Today, trafficking in human beings for the purpose of committing crimes is a reality, even if it is difficult to measure its extent due to the invisibility of the victims. By recruiting minors because of their precarious economic, social and administrative situation, and because they are unaware of their rights, traffickers are able to shift the burden of the criminal justice system onto minors rather than adults. This is a particularly lucrative form of exploitation that takes many different forms: pickpocketing, burglary, theft, sale of drugs, sale of cigarettes, sale of counterfeit goods, charity scams, etc. To combat it effectively, we need to prevent it among potential victims and crack down on those who profit from crime. Sanctioning victims of trafficking fuels the process.

3 / Protection must come first

The hold exerted on the victim of trafficking may be indirect or psychological, taking the form of debt bondage, threats to report to the authorities or other subtle means, such as abuse of a position of vulnerability. It is essential that the non-punishment provision is applied in practice as soon as the victim is detected by the authorities, in order to offer effective and comprehensive protection.

Victims must be immediately removed from the criminal justice system as offenders and must be protected as victims.

Furthermore, non-punishment remains in force until the victim is fully protected from prosecution and conviction.

When protection fails, the judicial authorities themselves must be able to confirm the victim’s lack of responsibility.

The obligation not to punish also applies to detention. Detention should end as soon as the situation of trafficking is identified and the victim should be taken into care if necessary in a specialised structure. Detention compromises the physical, psychological and social recovery of victims and can lead to an accumulation of trauma, suicidal behaviour and post-traumatic syndrome, as well as secondary victimisation.

However, in many countries the principle of non-punishment is not applied.

4 / Non-punishment training for all professionals is imperative

Investigating, prosecuting and judicial authorities and legal practitioners should be trained in the identification of trafficking in order to be able to apply the principle of non-punishment. Moreover, if victims are identified at an early stage and receive the protection and assistance to which they are entitled by virtue of their status as trafficked persons, they may also be in a better position to cooperate with the authorities in the investigation and identification of traffickers by providing information or evidence or even by acting as witnesses in criminal proceedings against them.

5 / We must prioritise the rights and well-being of trafficked persons

Non-sanctioning favours an approach focused on protecting the victim by recognising that victims of human trafficking are survivors of a crime, not criminals. By protecting victims, non-punishment encourages them to cooperate with law enforcement authorities in identifying and prosecuting traffickers, thereby strengthening the overall fight against human trafficking. Non-punishment also prevents re-victimisation: Punishing victims exacerbates their trauma, discourages them from seeking help and perpetuates the cycles of exploitation. Non-punishment is a crucial step in breaking these cycles.

***************************************************************************

To conclude (at the end of the event)

Non-punishment responds to the need to identify the true circumstances in which an offence is committed; it enables victims to be directed towards the safeguarding and assistance arrangements to which they are entitled; it encourages investigations into the crime of human trafficking, leading to an increase in prosecutions against traffickers and a decrease in prosecutions against victims for offences committed in the course of their victimization.

Non-punishment cannot be properly implemented by simply mitigating the penalties imposed, as this would not take into account the true condition of the victim under the trafficker’s control.

Legal and policy reforms are needed to review and amend existing legislation to ensure that victims of human trafficking are protected and treated as survivors and not as offenders. Specific provisions must be included that clearly exempt victims from criminal liability for involvement in unlawful activities that result directly from their exploitation.

Victim support systems must be strengthened. Establish comprehensive support systems that meet the specific needs of victims of trafficking: safe accommodation, health services, psychosocial support, legal assistance, access to education, training and employment.

Collaboration with civil society organisations, NGOs and relevant stakeholders must be strengthened to provide comprehensive assistance.

Training and capacity building for all professionals and volunteers involved is necessary for a victim-centred approach. Provide them with the skills to identify victims, handle cases sensitively and refer them to the appropriate support services.

International cooperation and information exchange mechanisms must be strengthened in order to facilitate the extradition of traffickers, promote cross-border investigations and establish cooperation frameworks to guarantee the protection and non-punishment of victims, regardless of their location or nationality.

Michel Veuthey

Merci, Geneviève. Thank you for these important remarks. Now, our second speaker is Virginia Gamba de Potgier, Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Children in Armed Conflict. She kindly provided us with a video statement from New York.

Virginia Gamba

Thanks to the Sovereign Order of Malta and co-organizers for the invitation to contribute to today’s discussions on non-punishment of human trafficking victims. My mandate monitors the six grave violations against children in armed conflict, including recruitment and use, rape and other forms of sexual violence, killing and maiming, attacks on schools and hospitals, abduction, and the denial of humanitarian access.

In 2022, the United Nations verified an overall number of 27,080 grave violations against children, including 2,880 that had occurred prior to 2021, but were only verified in 2022. A total of 18,890 children were victims of at least one of the four grave violations affecting individual children. Recruitment and use, killing and maiming, rape, and other forms of sexual violence and abduction are on the increase. At least 2,330 children were victims of multiple violations. Due to their interconnected and multi-layered nature, I have been more increasingly concerned with the linkages between these violations and human trafficking.

This is particularly because the rising cross border dimension of conflict poses an additional threat to the protection of children. And in cases of abduction, for instance, some violations could serve as a precursor for human trafficking.

I welcome your focus on the protection of victims of human trafficking, as oftentimes we witness that children as persons under 18 years of age per Article 1 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) suffer violations despite their status as minors. In 2018, with the adoption of its Resolution S/RES/2427 (2018) on children and armed conflict, the UN Security Council established that the children who have been recruited in violation of applicable international law by armed forces and armed groups and are accused of having committed crimes during their association should be treated primarily as victims of international law violations. This was in the context of the treatment of children in detention.

But it is important to note, as the Council reminded Member States of their obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), and this provision relates to the principle of non-punishment being discussed in your event today. In promoting a comprehensive framework for developing and implementing non-punishment policies that prioritise the rights of survivors of human trafficking, I call your attention to several key considerations regarding children affected by armed conflict specifically.

First and foremost, children who have suffered violations and abuses should be recognised as survivors of crimes and offered proper treatment. We must ensure that children who are released or escaped captors should be adequately supported and reintegrated safely back into their communities, that their specific needs are addressed in a comprehensive and sustainable way, while being mindful of age and gender specific needs, and that no measures taken by any actor are re-victimizing or re-traumatizing in any way.In the course of these efforts, we must also dedicate adequate child protection capacity in the form of human and financial resources.

We must also work together to raise awareness of the importance of registering children at birth, granting them the right to identity in accordance with Article 8 of the Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC), which is a critical initial step to ensure children’s protection in context liable to trafficking and related violations and abuses. Every person under 18 years must be recognised as a child. As children are entitled to special protection under international human rights law, particularly under the Convention (CRC).

At the local, national, and regional levels, public awareness and early warning mechanisms can contribute to prevention efforts against grave vio lations such as abduction, including its links to trafficking and generic violence against children.

We must also enhance our understanding and knowledge of the linkages on a deeper and more systematic level. This is why the Special Rapporteur on human trafficking, especially women and children, and I, are commencing a dedicated study to further analyse the nexus between trafficking of children and grave violations. And to improve the way we address the links between abduction and human trafficking purposes, and those between these two evils and other violations monitored through the “Children and Armed Conflict Agenda”,such as recruitment and use and rape and other forms of sexual violence.

Finally, I would like to draw your attention to the Guidance Note on Abduction my office launched last July in the presence of the Special Rapporteur aimed at our monitors on the ground, which is in part a tool for understanding and refining the definitions of abduction, particularly when examining cross border contexts, including on child trafficking and its linkages to abduction and other grave violations.

I encourage you to reference the Guidance Note available on my office’s website (childreninarmedconflict.un.org) in your work, as we are hoping that it could become the initial step in interagency and our programmatic discussions in the quest to understand and combat trafficking.

In considering prevention of re-victimisation of the victims of human trafficking, let us take into account that many of these victims are children.

Thank you very much.

Michel Veuthey

Thank you, Ms Gamba, for highlighting the importance of the non-punishment principle for children in situations of armed conflict. Our third speaker is Patrick Eba, UNHCR Deputy Director for Protection.

Patrick Eba

Talking Points for DD-DIP

HRC 53rd Session

Side event on Non-Punishment of Victims of Human Trafficking: Enhancing International Protection for Refugees and IDPs in the Perspective of Global Refugees Forum

Human Rights Council, 4 July 2023

Statement by Patrick Eba, Deputy Director, Division of International Protection

I would like to start by expressing UNHCR’s appreciation to the Permanent Mission of the Sovereign Order of Malta and Caritas for inviting us to speak during this important event.

[1] In 2022, for the first time, the world passed the symbolic mark of 100 million people forcibly displaced. This unprecedented high level of displacement is driven by conflict, violence, and persecution. New conflicts in countries such as Ethiopia, Ukraine and Sudan compound protracted and decades-long situations of forced displacement.

When people are forced to flee, whether internally or across borders, frequently along unsafe routes, traffickers can sometimes seem to be offering solutions. Recent data compiled by the Protection Clusters in 32 countries affected by displacement, reveals that in 65%, trafficking is a moderate to extreme risk. Often, trafficking is not a single phenomenon in situations of displacements. The risk of trafficking is associated with multiple-related risks and vulnerabilities including severe and extreme risks of gender-based violence, and risks of early and forced marriage and forced recruitment, including of children.

Increasing numbers of the world’s forcibly displaced and stateless people face poverty, discrimination, and marginalization, which in turn expose them to risks of trafficking. We need to reinforce protection for them.

[2] Trafficking affects people at different stages of their displacement. We must be alert to the trafficking risks from the outset of crises and recognize the patterns of human rights violations and abuses typical of trafficking.

Across all regions, pressures to control borders and migration often have serious unintended consequences, including detention and refoulement. Denial of access to asylum procedures or lack of mechanisms for the identification of victims of trafficking often lead to denial of rights with dramatic consequences.

Where no safe pathways to protection exist for people seeking safety, resorting to smugglers or using other clandestine means is often the only way refugees can seek asylum and access the international protection to which they are entitled. They may find themselves at the mercy of ruthless smugglers and traffickers who exploit their vulnerability and take advantage of their insecurity to charge high prices to move desperate refugees seeking safety and protection.

For refugees and internally displaced people living in camps or urban settings in protracted situations — trafficking risks often increase over time. For example, in Bangladesh, risks of trafficking are exacerbated for Rohingya refugees without legal status, no right to work and restrictions on movements outside camps, on education and livelihood opportunities.

Women and girls, in particular, are recruited for domestic work or as hotel maids but then trafficked for domestic servitude, forced labour and sexual exploitation both within Bangladesh and transnationally.

In the displacement and crisis contexts where we serve, for example, in the East and Horn of Africa, in the Sahel and along the routes to Central and Western Mediterranean, in Southeast Asia, there are hundreds of recorded trafficking cases. For asylum-seekers and refugees who flee in search of safety or when moving onward due to the lack of access to effective protection or, trafficking risks persist. UNHCR’s initiative entitled ‘Telling The Real Story’ collects testimonies of survivors and provides communities with trustworthy information on the risks of such dangerous journeys. UNHCR and our partners work tirelessly to document the abuses, identify those who have suffered harm, map available protection services and ensure victims/survivors referral and access to them.

[5] Seeking asylum is not an unlawful act. It is a universal human right. The exercise of this right cannot and should not be criminalized.

This is the rationale behind Article 31 of the 1951 Convention, which deals with the non-penalization of refugees for irregular entry. This provision is central to refugee protection. It serves to ensure that refugees and asylum seekers are able to access and exercise their human right to seek asylum without being penalized for breaches of immigration laws.

While Article 31 of the Refugee Convention does not provide blanket scope for irregular entry for refugees and asylum seekers in all circumstances, it does articulate specific parameters that should be interpreted broadly and in good faith. Non penalisation of asylum seekers and refugees will directly contribute to non-penalisation of those trafficked beyond borders.

[6] Much more is needed to address the protection needs of survivors and ensure their access to international protection where needed.

In 2006, UNHCR published its Trafficking Guidelines[1], defining UNHCR’s engagement with victims of trafficking and persons at risk of trafficking whose claim to international protection falls within the refugee definition. More recently, the Global compact on refugees has also focused on supporting States to identify and refer victims of trafficking to appropriate processes and procedures, including for the identification of international protection needs.

Yet, across all regions, challenges remain in ensuring access to asylum procedures and accompanying protections for victims and persons at risk of trafficking.

Some promising practices exist. For example, in Italy, UNHCR and the National Asylum Commission developed the Guidelines on Identification of Victims of Trafficking among applicants for international protection. Significant numbers of potential victims (i.e. persons for whom there are grounds to believe that they may have been trafficked) were detected, about 10.400 in the period 2018 to June 2020.

[7] We need to continue to support States in fulfilling their international obligations of refugee protection and prevention of trafficking and victim protection.

This requires proactive prevention. This means providing refugees with safe routes of admission to seek protection to avoid risky journeys facilitated by smugglers and traffickers.

Proactive prevention also means helping forcibly displaced persons access sustainable solutions, providing them with opportunities to work, enrol children in school, support the host communities and integrate locally.

Securing solutions includes improving access to complementary pathways to give refugees more routes to protection, such as reuniting with families and accessing scholarships and employment opportunities in third countries. When people have access to safety and opportunities, and when solutions are real, they become more resilient and self-reliant.

Consistent and effective implementation of these prevention, solutions and complementary approaches will save lives and improve dignity by cutting the business model of traffickers who will not be able to capitalize on vulnerabilities. The Global Refugee Forum in December will provide an opportunity to advance commitment by States and other stakeholders on these critical issues.

Michel Veuthey

Thank you, Mr. Eba, for reminding us of the link between non-punishment of human trafficking victims and refugees. Our next speaker Dr. Charlie Lamento, US Lawyer, Sollicitor in England and Wales, Registered European Lawyer (Czech Republic), UN Permanent Representative for Global Hope Network

Charlie Lamento

Human Trafficking Talking Points

Case Studies

- The average annual profits generated by 1 woman via forced sexual servitude aka prostitution is est. ($100,000) (Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)

- “Sexploitation” can yield a return on investment ranging from 100% to 1,000%, while an forced laborer can produce more than 50% profits

- Netherlands: Investigators calculated the profit generated by 2 sex traffickers from a number of victims. 1 trafficker earned $18,148 per month from 4 victims (for a total of $127,036) while the 2nd trafficker earned $295,786 in the 14 months that 3 women were sexually exploited according to the OSCE.

- Germany: Forced labor saves labor costs: In one case, Chinese kitchen workers were paid $808 for a 78-hour workweek in Germany. According to German law, a cook was entitled to earn $2,558 for a 39-hour workweek according to the OSCE.

Alarmingly Low Number of Prosecutions/Convictions of Human Traffickers

- The present day tactics and strategies are not working, as the number of criminal prosecutions and convictions for human traffickers and their accomplices remain extremely low globally.

Globally

- Estimated in 2017, 17,880 offenders were prosecuted worldwide, and only 7,045 were convicted = the majority of human traffickers are neither apprehended nor prosecuted. (US State Department (2018) Trafficking in Persons Report)

- Estimated in 2018, only 743 persons investigated in 10 countries — 183 persons prosecuted in 8 countries - 70 persons convicted in 7 countries. (UNODC Global Report on TIP 2018). Result: the risk for traffickers to face justice is extremely low

Europe

- 2015–2016 European Union MSs reported 5979 prosecutions and 2927 convictions for trafficking in human being (EU Commission Second report on the progress made in the fight against trafficking in human beings (2018) as required under Article 20 of Directive 2011/36/EU on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims 3/12/2018)

- MSs/WHO should declare that pornography is public health crisis – especially as it pertains to children.

- See 16 US state legislatures declarations

- People addicted to pornography show similar brain activity to alcoholics or drug addicts.

- MRI scans of test subjects who admitted to compulsive pornography use showed that the reward centers of the brain reacted to seeing explicit material in the same way as an alcoho lic’s might on seeing a drinks advert.

Global Hope Network Int. Rue de Varembé 1, Genève Switzerland 1202

Email: charlie.lamento@ghni.org - Web: https://www.globalhopenetwork.org/

Swiss Federal Commercial Register No.: CHE 110.622.356 — Genève Canton

- See: https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/brain-activity-in-sex-addiction-mirrors-that-of-drug-addiction

- Which means, like drug/alcohol addicts, porno addicted persons must continue to seek out more graphic/violent sexual images to keep and increase their brain serotonin levels — and eventually acting out these deviant sexual desires with others – including children and those prone to exploitation.

See South Korea’s Effective Porn Blocking Method

- In February 2019, South Korea enacted a controversial new method to block illegal content, specifically pornography and pirated material, accessed through Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) websites.21 The new scheme uses Server Name Indication–filtering (SNI), which entails monitoring the unencrypted SNI that shows which HTTPS sites a user is visiting.22

- See: https://freedomhouse.org/country/south-korea/freedom-net/2022

The international community must enact a universal standard/test to identify post-traumatic stress syndrome (CPSD) that would reduce the prosecution trafficked victims

- Studies indicated that an average of 41% of survivors of modern slavery and human trafficking had CPTSD

Michel Veuthey

Thank you, Dr. Lamento, for your insightful remarks. Now, our fifth speaker is Dr. Olivia SMITH, Executive Director of the Caribbean Anti-Human Trafficking Foundation. She will give us a video-recorded statement

Olivia Smith

His Excellency, Michel Veuthey, Ambassador of the Sovereign Order of Malta to combat human trafficking.

Other Excellencies, officials, ladies and gentlemen, good morning.

Human trafficking constitutes a severe and intricate form of exploitation, cruelly robbing individuals of their rights, freedoms, and human dignity. It represents an affront to our collective humanity, inflicting harm on individuals and communities worldwide, compromising national and economic security, and eroding the rule of law. This reprehensible practice has no place in our global society. Despite the ratification or accession of over 175 nations to the United Nations Protocol to prevent, suppress, and punish trafficking in persons, which meticulously defines human trafficking and establishes obligation to deter and combat this crime, progress remains uneven. Victims of human trafficking frequently bear the legal burden of illicit activities committed as a direct result of their trafficking circumstances. These actions not only encompass specific forms of exploitation, such as prosecution or engagement in illegal work, but also the associated immigration, administrative and civil offences.

However, it is crucial to underscore that the spotlight of investigations and prosecutions should shine largely on the criminal actions of traffickers. These perpetrators, not their victims, are legally accountable for the precise exploitative forms enforced upon the victims. A lack of this nuanced understanding by States results in risk of re-traumatising of victims who may be wrongfully arrested, prosecuted, and convicted for crimes committed while engineered in the trafficking system. Such misapplication of the law could detrimentally affect victims, infringe upon their rights, and discourage collaboration with legal proceedings and compromise the wider justice system.

Notably, this situation continues to disproportionately impact women and girls worldwide. In the landscape of human trafficking victim rights, the principle of non-punishment is the cornerstone of the human rights protection in international, regional, and domestic laws. This concept developed substantial prominence as it relates to the invaluable legal right of victims to protection. Prosecuting trafficking victims flagrantly violates their rights to protection.Non-punishment provisions thus serve the dual purpose of extending the legally deserved protection to trafficking victims and preventing re-trafficking, while simultaneously ensuring that the actual perpetrators are brought to justice. This approach aligns with the objectives outlined in the Preamble of the Palermo Protocol.

Moving forward, Governments should abstain from penalising or prosecuting trafficking victims for all lawful activities forced upon them by their traffickers. This principle should shield victims from legal accountability, from actions they were coerced to do by their traffickers. If a victim has been wrongfully penalised or punished, Governments should vacate their convictions and expunge their records.

The post COVID 19 era offers States, international organisations, and communities a great opportunity to evaluate and re-energize actions on this issue. Key initiatives should include the development of statutory defenses and national law, training across the judicial systems and law enforcement, and assistance services to support victim identification and the integration of non-punishment principles into anti trafficking frameworks. Applying these principles in a non-discriminatory age and gender responsive manner is an imperative step towards meeting State social and legal obligation towards victims of human trafficking.

Thank you.

Michel Veuthey

Thank you, Dr. Smith. Our next speaker is Dr. Andrea Salvoni, OSCE Acting Coordinator for Combatting Trafficking in Human Beings. He shall give us a short video message on the role of OSCE in promoting the non-punishment principle.

Andrea Salvoni

Michel Veuthey

Thank you, Andrea.Now we have pleasure to give the floor to Ena Lucia MARIACA PACHECO and Silvia De Rosa, from INTERPOL.

Ena L. Mariaca Pacheco

Ladies and gentlemen, Distinguished guests,

Let me begin by thanking the Sovereign Order of Malta, Caritas Internationalis, Secours Catholique, and Costa Rica for inviting us to this important meeting.

My name is Ena Lucia Mariaca Pacheco, and my colleague Silvia De Rosa are here before you today on behalf of the International Criminal Police Organization, Interpol, to address an important matter that demands our unwavering attention and collaborative efforts.

The issue at hand is the non-punishment of victims of human trafficking, the urgent need to enhance victim protection, foster collaboration across all sectors, ensure safeguarding, building capacity, and strengthen international cooperation.

Today, we assert that victims of human trafficking should not be treated as criminals. They are victims and survivors, individuals who have endured unimaginable suffering and trauma.

It is through this safeguarding lens that Interpol advocates for the non-punishment of victims and a shift in focus from criminalization to victim-centered approaches.

The Human Trafficking and Smuggling of Migrants Unit at INTERPOL is under the Vulnerable Communities Sub-directorate. This sub-directorate, differently from others, as it has a focus on crime areas that place people in vulnerable situations.

Therefore, it is imperative that in the fight against these crimes, it is not the only priority for law enforcement to dismantle these criminal networks, but also safeguard the victims that have been affected by them.

We need to remember that victims of human trafficking can be any gender and any age – and I would like to highlight the need to not forget the countless men and boys of these crimes. At INTERPOL we recognize this and aim to protect all victims.

INTERPOL has been working on developing policies and procedures for the protection and assistance of victims, it has produced internal guidelines in this regard, and it is continuously assessing how these procedures can be enhanced.

In accordance with INTERPOL’s Constitution, which has been drafted in the spirit of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, INTERPOL-facilitated operations should reach their objectives while not further harming the human rights and dignity of vulnerable communities.

Law enforcement agencies are often the first ones to have contact with a victim of human trafficking, and this first approach is crucial for good assistance and development of the case.

An official must be aware of the impact of this crime on the victims, and it is their responsibility to identify which kind of immediate assistance is needed and properly refer the victim.

Silvia will now further explain our safeguarding framework in our global operations and projects.

Silvia De Rosa

In the framework of INTERPOL HTSM operations, INTERPOL stresses to national law enforcement agencies the importance of having a plan to ensure victims and vulnerable migrants that may be identified during the operation will receive the protection and assistance they need.

INTERPOL asks that this be clearly detailed in all national operational plans.

A session on victim protection and assistance is delivered during the pre-operational training to national law enforcement officers that will be involved in the operation.

INTERPOL has an agreement with IOM since 2014 that allowed great collaboration between the two organizations. IOM has a complimentary mandate to INTERPOL’s, which allows it to provide assistance to victims when national institutions cannot.

Indeed, in the case where national authorities lack the necessary resources to provide adequate support to victims and vulnerable migrants and do not have local/national partners that can provide full support, National Central Bureaus are invited to notify INTERPOL of this need and request its support in liaising with IOM. INTERPOL General Secretariat then coordinates with IOM HQ to find solutions.

An example of this collaboration with IOM is Project AKOMA jointly implemented in 2015. The operation organized within this project allowed the rescue of 75 children victims of human trafficking.

More recently, in 2021, Operation PRISCAS, organized within the framework of the THB West Africa Project rescued a total of 90 victims, 56 of which were children and 34 adults. In this case, victim assistance has been provided through the direct collaboration of the local law enforcement agencies involved in the operation and local institutions and NGOs.

This project is an example of the success that can be reached through the implementation of projects that combine the capacity building component, offering specialized training on THB, on INTERPOL’s policing capabilities and on dissemination of knowledge (train-the-trainer); with the operational component, supporting investigations on THB throughout the whole length of the project. Judiciary is involved too, at the prosecution level especially, which is crucial to progress with the criminal case of the traffickers after the arrest, but often also for the official identification of victims and their access to justice.

In conclusion, INTERPOL stands committed to the non-punishment of victims of human trafficking, and to achieve these objectives mentioned above, we must work collaboratively to create a comprehensive support system encompassing short and long-term needs to safeguard and support victims and survivors, regardless of age, gender, or ethnicity.

Thank you.

Michel Veuthey

Thank you both for sharing the views from INTERPOL HQ and your field experience.

I would like to extend my thanks to all the panelists present here today. We all share a common understanding: traffickers must be apprehended, prosecuted, and subjected to legal measures, whereas victims should be protected by the law and provided with assistance to reintegrate into society.

In conclusion, non-punishment is a crucial element in protecting victims of human trafficking and preventing their further victimization. By recognizing the vulnerability of victims, encouraging reporting, promoting rehabilitation, and implementing comprehensive support systems, societies can ensure that victims receive the protection and assistance they need to rebuild their lives. We hope that this event provided a contribution to guide policymakers, governments, and stakeholders in developing and implementing effective non-punishment policies that prioritize the rights and well-being of trafficking survivors. Victims should be protected and provided with assistance to reintegrate into society.

[1] UNHCR Guidelines on International Protection No7 on the application of Article 1A(2) of the 1951 Convention and/or 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees to victims of trafficking and persons at risk of being trafficked