Status of the issue

Surrogacy (GS) is the name given to the technique known as “surrogacy”. It belongs to Assisted Human Reproduction[1]. With its own characteristics, it is part of an international reproductive market. It is prohibited in France and many other countries.

GPA uses a woman to carry the child during pregnancy so that the so-called “intention parents” can recover the child once born, so that it is considered their own. This is reflected in an agreement between this woman and the parents of intent. The child is almost always given to them for a price. Private intermediaries have been set up to establish these agreements and guarantee their execution.

GPA comes in several forms: insemination of the surrogate mother with the spermatozoa of the intention father who will also be the biological father, or with those of a donor; in vitro conception of a human embryo, from the gametes of the intention parents, or from one of the parents with one donor, or from two donors, which will be implanted in the uterus of the surrogate mother.

Applicants are male/female couples whose wives cannot bear children, single men or couples of men, or even fertile women who, refusing the “inconvenience” of gestation and childbirth, resort to GS “for reasons of convenience” (CCNE, Opinion 126).

The Court of Cassation (judgment of 31 May 1991) stated as a principle that “the agreement by which a woman undertakes, even free of charge, to conceive and bear a child in order to abandon it at birth contravenes both the principle of the unavailability of the human body and the principle of the unavailability of the state of persons”. The Act of 29 July 1994 introduced article 16–7 into the Civil Code: “Any agreement concerning procreation or gestation on behalf of another is null and void.

To circumvent the French ban, French people go abroad, to a state where GS is authorised. On their return to France, they request that the child’s birth certificate, drawn up in the country of birth, be transcribed in the French civil status registers. Since 2015, the Court of Cassation has accepted the transcription when this act says reality: the parents are the “surrogate mother” and the biological father, according to the principle certa mater is[2]. In three judgments of 5 July 2017, the Court extended this principle by specifying that if the mother is not the “surrogate mother”, transcription cannot be authorised.

The father’s spouse can then apply to adopt the child. Since a fourth judgment of 5 July 2017, the Court of Cassation has accepted adoption (in this case simple) while the courts on the merits have not followed it and have rejected applications for adoption (in this case in plenary session) (Paris Court of Appeal, 30 January 2018). Until this decision of July 5, 2017, the Court of Cassation refused adoption, simple or plenary, since the GPA, by organizing the removal of the surrogate mother — the woman who gave birth — in order to make the child adoptable, diverts adoption from its meaning: giving parents to a child who has been deprived of it (by the misfortunes of life and not by a contract).

Although French law invalidates any GPA agreement, its effects are, to a large extent, accepted in France by the courts[3]. Therefore, it is difficult for France to fight against GS.

Questions this raises

The National Consultative Ethics Committee stresses that “of all MPA procedures, GS is the only one that separates the child from the woman who bore it, and the only one also capable of completely dissociating biological transmission (genetic via gametes, epigenetics via pregnancy) and social transmission (parental care of the child at birth), since parents of intention may not participate in any stage of procreation and gestation[4]”.

GPA establishes a rupture of the gestational bond contracted between the child and the woman who bore it. If the surrogate mother has been inseminated, there is a disjunction between the biological gestational mother and the educational mother of intention. If the mother of intention has donated her oocyte so that the embryo can be conceived and implanted in the uterus of the surrogate mother, there is a disjunction between the gestational mother and the mother of intention, who is also the biological mother. The disjunction is even stronger when GS is performed for the benefit of a couple of men: the child, separated from its gestational mother, is also motherless. It would be illegitimate to legalize the birth of children without mothers.

However, gestation cannot be erased in the construction of the child. Epigenetics[5] shows that the biological (and psychological) environment during gestation is not without importance for the child who will be born and develop. The child abandoned by the surrogate mother immediately after birth therefore suffers harm. Moreover, child abandonment is prohibited by law.

To avoid an excessive link between the surrogate mother and the child, conventions favour or even oblige that the oocyte does not come from the surrogate mother, and impose (in the United States) that the parents of intention be recognized as the parents before the birth, which causes an administrative act of birth not corresponding to the reality of the facts: the registered mother is not the woman who gave birth. Again, this is harmful to the child.

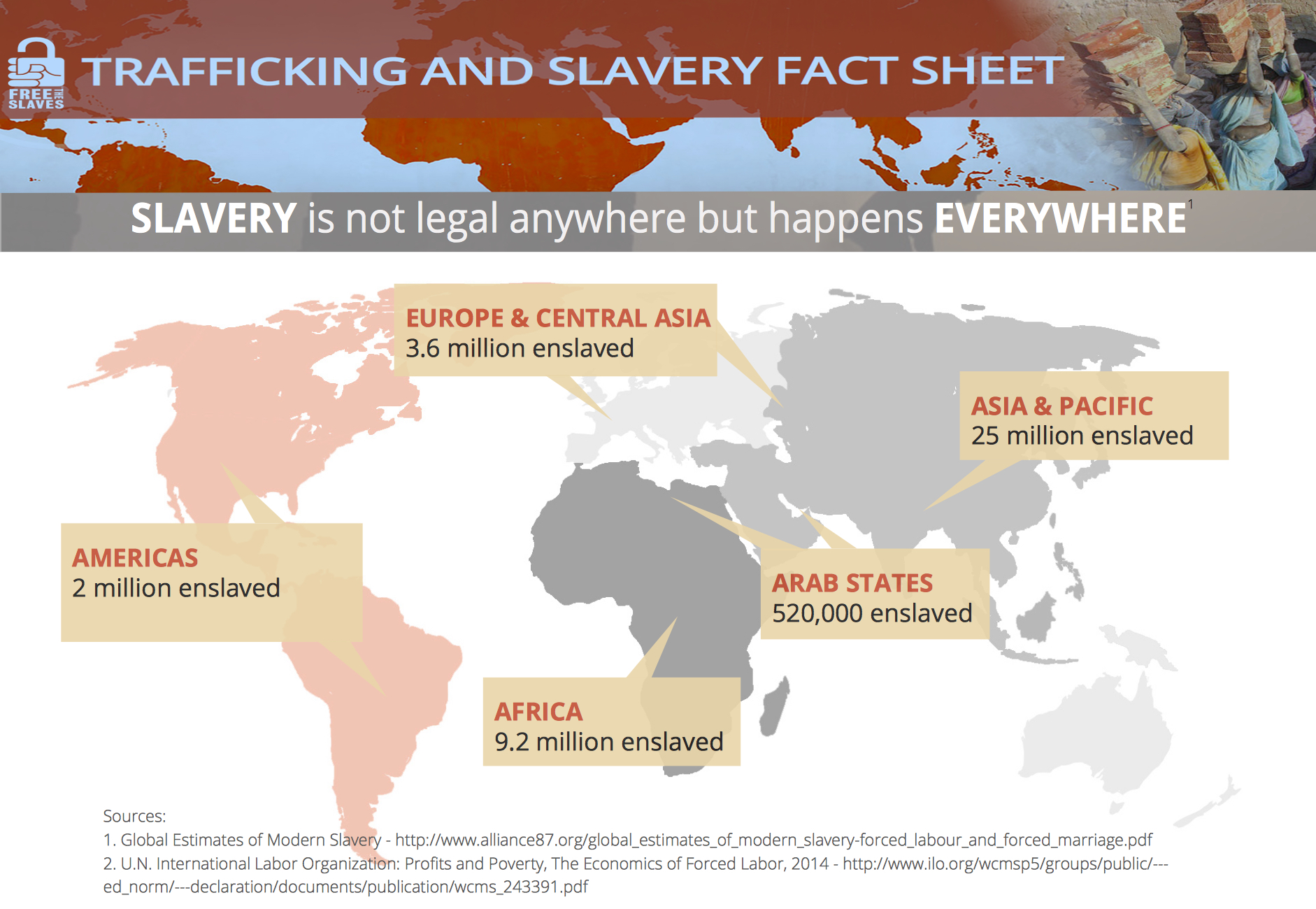

GPA uses a woman’s body during the nine months of gestation, most of the time for remuneration or financial compensation, without always ensuring her physical and psychological integrity (especially in Asia). They are often poor women who need money. This “use” of a woman is contrary to her dignity and the principle of the unavailability of the body.

We speak of “ethical GPA”: it would be realized free of charge thanks to a woman friend or member of the family, who offers her body to carry the child of a couple who could not. In fact, GS always has a cost, which claims either compensation or compensation. In addition to the serious ethical questions, there are also risks due to the proximity of the two mothers in everyday life: will the surrogate mother not be intrusive in the couple’s life by considering that the child is also hers?

GS makes a child’s parentage unreadable if more than two adults are involved (up to five adults) in its existence and development before and after birth.

It is illegitimate to pay a sum to have a child, according to a contract. Even if GS were free, there would still be a contract organizing the disposition of the child as property. However, “in the GS contract, the body and the person of the child are in a position of object of the contract, incompatible with the general principles of law. This object position has effect because the contract must provide for what happens if the object of the contract does not conform to what is expected.

The desire for a child is commendable and the suffering due to medical infertility is to be accompanied[7]. But this desire cannot become a “right to the child”, especially in the face of the serious harm that GS creates.

Since 1987, the Church has been negatively discernible about GS: “Surrogacy represents an objective breach of the obligations of maternal love, conjugal fidelity and responsible motherhood; it offends the dignity of the child and his right to be conceived, borne, brought into the world and educated by his own parents; it creates, to the detriment of families, a division between the physical, psychological and moral elements that constitute them (8).

—————————————————–

[1] Voir J.-R. Binet, Droit de la bioéthique, LGDJ, 2017, p. 174–176.

[2] La femme qui accouche est la mère. Ce principe ne rend pas compte de la dissociation entre génétique et gestation.

[3] Voir J.-R. Binet, « Gestation pour autrui : le droit français à la croisée des chemins », n. 9 – septembre 2017, LEXISNEXIS.

[4] Avis n. 126 du 15 juin 2017. Voir aussi les Avis n. 90, du 24 novembre 2005 et n. 110, du 1er avril 2010.

[5] Par la génétique, on étudie le génome et son environnement biologique. Cet environnement a une telle influence sur l’expression des gênes (et non sur leur structure interne) qu’il mérite d’être étudié pour lui-même : c’est l’épigénétique.

[6] Comité Consultatif National d’Éthique, Avis n. 126, p. 34. Cet avis expose quelques situations dramatiques sur la GPA.

[7] L’accompagnement d’un couple hétérosexuel infertile n’est pas le même pour un couple homosexuel. Voir l’arrêt de la Cour Européenne des Droits de l’Homme, du 15 mars 2012, n. 25951/07, qui ne juge pas discriminatoire le refus de la France à la demande d’un couple de femmes pour pouvoir recourir à la PMA. (Voir fiche sur l’assistance médicale à la procréation).

[8] L’accompagnement d’un couple hétérosexuel infertile n’est pas le même pour un couple homosexuel. Voir l’arrêt de la Cour Européenne des Droits de l’Homme, du 15 mars 2012, n. 25951/07, qui ne juge pas discriminatoire le refus de la France à la demande d’un couple de femmes pour pouvoir recourir à la PMA. (Voir fiche sur l’assistance médicale à la procréation).